This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition.

“Mussa! Shoot the ball!”

“DaVaughn! Just lay the damn ball in!”

“Johnnie! What was that?”

“Take the ball and do it, Chucky. Now!”

“Hey … hey … come over and talk to me. How is that a foul? Tell me, how is that a foul? Did you even see the play? (Expletive)!”

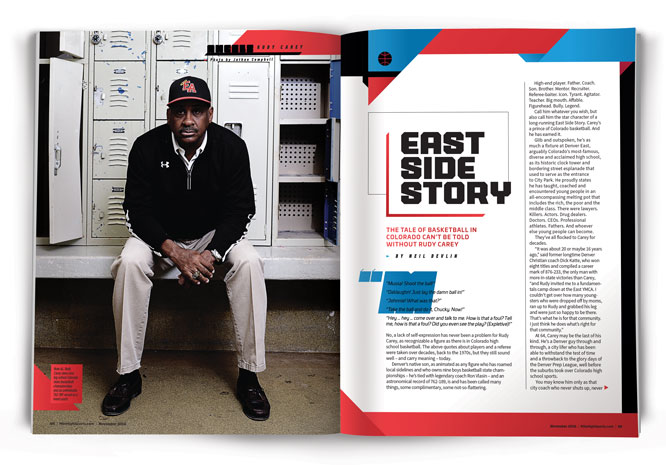

No, a lack of self-expression has never been a problem for Rudy Carey, as recognizable a figure as there is in Colorado high school basketball. The above quotes about players and a referee were taken over decades, back to the 1970s, but they still sound well – and carry meaning – today.

Denver’s native son, as animated as any figure who has roamed local sidelines and who owns nine boys basketball state championships – he’s tied with legendary coach Ron Vlasin – and an astronomical record of 762-189, is and has been called many things, some complimentary, some not-so-flattering.

High-end player. Father. Coach. Son. Brother. Mentor. Recruiter. Referee-baiter. Icon. Tyrant. Agitator. Teacher. Big mouth. Affable. Figurehead. Bully. Legend.

Call him whatever you wish, but also call him the star character of a long-running East Side Story. Carey’s a prince of Colorado basketball. And he has earned it.

Glib and outspoken, he’s as much of a fixture at Denver East, arguably Colorado’s most-famous, diverse and acclaimed high school, as its historic clock tower and bordering street esplanade that used to serve as the entrance to City Park. He proudly states he has taught, coached and encountered young people in an all-encompassing melting pot that includes the rich, the poor and the middle class. There were lawyers. Killers. Actors. Drug dealers. Doctors. CEOs. Professional athletes. Fathers. And whoever else young people can become.

They’ve all flocked to Carey for decades.

“It was about 20 or maybe 16 years ago,” said former longtime Denver Christian coach Dick Katte, who won eight titles and compiled a career mark of 876-233, the only man with more in-state victories than Carey, “and Rudy invited me to a fundamentals camp down at the East YMCA. I couldn’t get over how many youngsters who were dropped off by moms ran up to Rudy and grabbed his leg and were just so happy to be there. That’s what he is for that community. I just think he does what’s right for that community.”

At 64, Carey may be the last of his kind. He’s a Denver guy through and through, a city lifer who has been able to withstand the test of time and a throwback to the glory days of the Denver Prep League, well before the suburbs took over Colorado high school sports.

You may know him only as that city coach who never shuts up, never sits down and seemingly gets all of the good players on the way to winning championships. But interesting? You bet. Count the ways:

He was born at Colorado General Hospital, now operated by the University of Colorado. Raised near the corner of 35th and Fillmore, which Carey said “later became the gang zone,” he attended Harrington Elementary, which is still in existence after a move. While there he had peers such as Sayyid Abdal-Rahman (formerly known as Rayford Tillis), Chuck Williams and Larry Farmer. The great Alex Burrell was one of Carey’s teachers.

“My parents gave us everything that money couldn’t buy,” he said. “We had love and compassion and didn’t always have the material things.”

His mother, Ruth, will turn 90 in December.

He was bussed to Smiley Middle School and only had half-days in school for a bit.

“We had too many kids,” Carey said.

As well, parents not only watched out for their kids, but their neighbors’ children, too.

“We had a sense of community when I grew up,” Carey said. “The neighbors would whip your butt, then call your house and you’d go home and get a butt-whipping … now, we don’t have that collaborate of discipline.”

He was an all-state guard at Denver East, class of 1970, and went on to play at Colorado State. Rick Williams and Bobby Caton were some of the Rams seniors when he was a freshman.

He worked for the Denver Housing Authority for a year and even had a tryout with the Denver Nuggets, who had David Thompson and Monte Towe on their roster. Larry Brown was the coach.

He was at Western State in Gunnison for a year, where he coached its junior varsity team and got certified as a coach. He served as an assistant at George Washington for revered DPL coach Joe Strain for two seasons, beginning in 1977. In 1979 he took over at Manual, and then returned to Denver East in the early 1990s where the greatest coaching run in big schools in state history continues.

It didn’t, however, start off with a bang.

“It was tough; the expectations were so high at Manual,” Carey said. “There was so much pressure to win at Manual and there was always the rivalry of East-Manual. I wasn’t received well because I was an East grad, not a Manual grad. The Manual community was not too happy about it.”

The Manual community eventually got over it. Chucky Sproling, who still owns the state record of 74 points in a single game and went on to St. John’s, arrived in the mid-1980s and the Thunderbolts took off. Carey would coach an enviable string of players, significant all-staters. Tommy Pace. Johnnie Reece. J.B. Bickerstaff. Kaniel Dickens. Sean Ogirri. Dominique Collier. Brian Carey, a nephew. And Carey’s teams would outduel a who’s who string of coaches in playoff rounds, including the finals. Vlasin. Abdal-Rahman. Terry Taylor, Sr. Gary Osse. Ken Shaw. Joe Ortiz. John Olander, Jr.

Name-dropping, counting victories and championships, and reminiscing about a childhood long ago aside, the one denominator common to Carey has been kids, generations of them that he has put first – every time.

“It’s always about kids for him, what’s best for them and putting their needs and aspirations first, and how to set them up for success,” longtime Angels athletic director and trainer Lisa Porter said. “He knows about every coach known to man. But he connects with the kids and gets them to be a contributor for that team. I’ve been around since 1996 and there’s always a college coach in the gym watching practice or talking to them. And it’s because Rudy’s into the kids.”

And the kids have been into Carey.

“It was great playing for him,” said Collier, a four-year Angels starter who’s set to begin his junior season at the University of Colorado. “He pushed all of us and he was more of, like, a friend coach. We got along with him outside of practice. On road trips, that made us a whole lot closer, at least for me personally with him. He’s a great coach and that’s why he’s one of the best in Colorado history.”

Carey has done a lot of it through discipline. And, as usual, he can offer several thoughts on the subject.

A man who used to deliver 500 newspapers per day in addition to teaching, coaching and being a family man – wife, six kids and two grandchildren – knows about working hard and being true to himself and his surroundings.

For example:

Sadly, he admits, “the majority of families have moved to Aurora. Basketball has shifted to Aurora other than ourselves and [George Washington]. The majority of the kids go to Aurora schools now in terms of basketball.”

When the Thunderdome opened at Manual in 1992 and centralized the big DPL games that drew large crowds and had previously been played at Metro State, “it gave us a sense of community.”

Shortly after, his move to East followed as “somebody was even telling me seven-to-eight years before that time that East was a bright light that lived in darkness. I can’t remember who told me. But we’ve always felt like we were a shining star for the community and not only successful on the basketball court … Pia Smith (the Angels principal at the time) and I graduated together and she called me and said she had an opening in basketball and ‘Are you ready to come to East?’ I said it was always my dream job.”

Parents? They try to mess with a guy who has Carey’s credentials, too. “I’ve gone from having 15 kids on the team and 14 didn’t have fathers in the home to other teams where many had both in the home.”

And race? “It has and hasn’t been a problem. The thing about athletics is that they have a tendency to block out racism. My biggest problem has been with black parents. I’ve had friends and other people who wanted me to wave a magic wand and make their kids great … a lot of them are so undisciplined and have no guidance.”

Primarily a physical education teacher, Carey also works with special-needs kids as well as those in Special Olympics. “Those kids, they give you everything they’ve got in spite of their challenges. I love them, everything about them – they give 100 percent and are 100 percent authentic.”

He’s also convinced the game “has regressed and so has the love for the game,” which may help explain his intensity. He coaches as if he’s trying to save it.

“Way back when I moved here, Jim Baggot was known for his press at Greely Central and it was the power in high school basketball,” Katte said. “John Wooden always had a 2-2-1 press. Everybody knows part of his system. Rudy Carey always has a press and his teams can play man-to-man defense when they have to. Defense is what keeps him solid.”

No question, Ortiz said, “he’s legendary. We played him three times in the finals. He’s extremely passionate, extremely competitive. He sets ridiculous expectations for excellence. He wants to win every year and his kids know that. That just doesn’t happen. I’ve always had tremendous respect for him.”

Shaw actually played against Carey. Twice. He starred at Merino and the two scrimmaged in the old prep all-star games against each other, then squared off again while Carey was a freshman at CSU (freshman weren’t allowed to play varsity) and Shaw was at Northeastern Junior College.

“He’s certainly unique,” said Shaw, who has 42 seasons on the bench and 714 victories, right behind Carey on the Colorado list. “And I don’t know if anyone else would have gotten out of his guys what he has. He has certainly had a remarkable career … I know that Rudy as a player was very similar to how he has been as a coach, very brash, very confident. That’s who Rudy is and I have great respect for him … Maybe we aren’t used to seeing that or how he coaches, but he certainly relates to kids. He has stood the test of time in a profession that tends to chew up people and spit them out. It’s hard to last for the long term.”

Michael Rogers got an inside peek. The former head coach at GW assisted with the Angels in 2013-14, when they won their last title, and now is entering his third season heading Grandview.

“When you have that many gold balls something is definitely working,” said Rogers. “I think the thing I found that year is that his kids just play harder than everybody else’s, just hard every second on the court and that gets them over the hump. That comes from practicing. They practice hard and are always going hard, they rarely come off the court. But at the same time that’s the mental togetherness that they have. He has the best players and he lets them take over and win. Seeing that, it added a little more into what I want to do.”

Olander, one of the few coaches to edge Carey in a state final, said he benefitted “from when I was a young coach and Rudy was very gracious, very complimentary. He always does something different. He has not been afraid to do what it takes to win. He’s not afraid to change up things defensively.”

Carey, who almost unbelievably has never sent a player to CSU and only one (Collier) to CU, also was the first in-state coach to go on large road trips in search of significant competition and team bonding. Who else but the Angels, who have played in Florida, California, Las Vegas, Utah, Topeka, Kan., Charlotte and Milwaukee, have played in Maui, which they did the past season?

“We’re trying to make our kids more worldly,” Carey said.

He also started the city charge of travelling to the suburbs, then welcoming those outside the city to play at the Thunderdome or in East’s quaint gym that made for hot hoops nights.

No, he never seriously considered “going to a higher level (to coach, although there were rumblings in the 1990s about his possibly joining the Globetrotters). No, I’ve been through dozens of governors and mayors, 16 principals and 20-some ADs. It has been a wonderful life. I’ve not gotten rich behind basketball, but I’ve met some of the most wonderful people in the world, some of the most beautiful, some of the worst people.”

As for how much longer he’ll be in it, Carey said it will be a maximum of three years in both teaching and coaching. And what’s to leave? He calls Angels principal Andy Mendelsberg “a visionary, who always wants our kids to have the best and be the best. We try to prepare them for life, not just basketball.

“I’m enshrined at East,” he added. “They can throw my ashes out on the field.”