This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition.

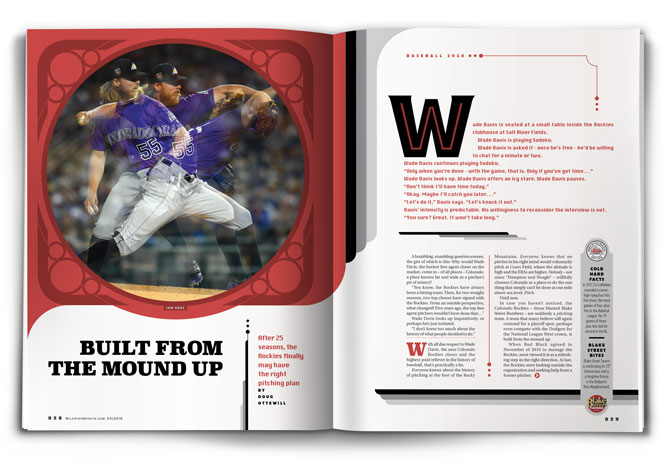

Wade Davis is seated at a small table inside the Rockies clubhouse at Salt River Fields.

Wade Davis is playing Sudoku.

Wade Davis is asked if – once he’s free – he’d be willing to chat for a minute or two.

Wade Davis continues playing Sudoku.

“Only when you’re done – with the game, that is. Only if you’ve got time…”

Wade Davis looks up. Wade Davis offers an icy stare. Wade Davis pauses.

“Don’t think I’ll have time today.”

“Okay. Maybe I’ll catch you later…”

“Let’s do it,” Davis says. “Let’s knock it out.”

Davis’ intensity is predictable. His willingness to reconsider the interview is not.

“You sure? Great. It won’t take long.”

A bumbling, stumbling question ensues, the gist of which is this: Why would Wade Davis, the hottest free agent closer on the market, come to – of all places – Colorado, a place known far and wide as a pitcher’s pit of misery?

“You know, the Rockies have always been a hitting team. Then, for two straight seasons, two top closers have signed with the Rockies. From an outside perspective, what changed? Five years ago, the top free agent pitchers wouldn’t have done that…”

Wade Davis looks up inquisitively, or perhaps he’s just irritated.

“I don’t know too much about the history of what people decided to do.”

“We don’t spend a lot of time and energy reliving history.” – Jeff Bridich

With all due respect to Wade Davis, the new Colorado Rockies closer and the highest-paid reliever in the history of baseball, that’s practically a lie.

Everyone knows about the history of pitching at the foot of the Rocky Mountains. Everyone, knows that no pitcher in his right mind would voluntarily pitch at Coors Field, where the altitude is high and the ERAs are higher. Nobody – not since “Hampton and Neagle” – willfully chooses Colorado as a place to do the one thing that simply can’t be done at one mile above sea level: Pitch.

Until now.

In case you haven’t noticed, the Colorado Rockies – those blasted Blake Street Bombers – are suddenly a pitching team. A team that many believe will again contend for a playoff spot, perhaps even compete with the Dodgers for the National League West crown, is built from the mound up.

When Bud Black agreed in November of 2016 to manage the Rockies, most viewed it at as a refreshing step in the right direction. At last, the Rockies were looking outside the organization and seeking help from a former pitcher.

When free agent closer Greg Holland signed with the Rockies not long after Black’s arrival, eyebrows were raised. At one point, Holland was considered one of the game’s best closers. However, he’d sat out the entire 2016 season recovering from Tommy John surgery. The respected reliever signing with Colorado came with an asterisk – it looked as if the Rockies and Holland were accepting a mutual risk, otherwise he might have landed elsewhere.

The Holland signing worked out well for both parties; behind a historically young staff that performed better than expected and Holland’s franchise-best 41 saves, the Rockies found themselves in the postseason for only the fourth time in club history. More notable than the playoff appearance was the fact that pitching was a huge, if not the biggest, reason why – an odd notion in Colorado to say the least.

Then, Wade Davis and Bryan Shaw signed.

In just two offseasons, three top pitchers had opted – on their very own – to become Colorado Rockies.

Huh?

If Wade Davis didn’t know the perception, the horror stories, or the cold, hard truth that surrounds the first 23 years of pitching and the Colorado Rockies, Jeff Bridich certainly did.

The realization that the Rockies had issues on the mound was not revolutionary. Everybody (other than, ahem, Wade Davis) knew that. But fixing the problem was an effort that began long before Bridich convinced Black to manage the team.

Those in the know all point to the same thing, a three-day meeting that’s now referred to as “the pitching summit.”

Sep 11, 2017; Phoenix, AZ, USA; Colorado Rockies starting pitcher Kyle Freeland (31) leaves the game with Steve Foster (56) after getting hit with a line drive in the fourth inning against the Arizona Diamondbacks at Chase Field. Mandatory Credit: Rick Scuteri-USA TODAY Sports

Three and a half years ago, not long after he became the general manager following the 2014 season, Bridich, along with pitching coaches Darren Holmes and Steve Foster, called timeout – then they called the so-called summit.

Bridich had been with the organization since 2004 and held various roles – managing the team’s minor league operations, then becoming the director of baseball operations and ultimately the director of player development. He knew the players already in the system, most importantly the pitchers and catchers, and he knew the coaches who coached them. He had ideas but chooses his words carefully when he’s asked, “What was going wrong?”

“Any answer to that question is a dangerous one because it dredges up history,” he says. “We don’t spend a lot of time and energy reliving history.”

There might have been “some issues with connectedness,” and there were times he didn’t believe everybody was “pulling on the same end of the rope at the same time.”

But, “In the history of baseball,” he’s quick to point out, “that has happened a billion times.”

Foster, who had been with the Kansas City Royals from 2010 to 2014, says, “The overwhelming credit goes to Jeff Bridich and his vision. I consider him a great visionary.”

Foster had a track record of his own that included a trip to the 2014 World Series. The next season, Foster’s first with the Rockies, the pitching staff he’d assembled and developed in Kansas City returned to the Fall Classic and won. Initially, Foster held the role of the Royals’ major league bullpen coach; in 2013 the organization promoted him to a special assistant to the general manager and pitching coordinator, where he oversaw the entire organization’s pitching staff from top to bottom. When Foster joined the Royals, the team’s bullpen was second to last in the majors in ERA (5.02), but it improved every year under his guidance.

“[I was] in charge of all the all the pitching coaches in the minor league [system] and 100-plus minor league pitchers,” he explains.

“That’s where ‘The Plan’ originated.”

While its origins may be traced back to Kansas City, Foster’s plan didn’t fully materialize until that all-important Rockies pitching summit.

“[We wanted] to go after hard four-seam guys, good spin rates on curveballs, sliders, mechanically sound guys.” – Steve Foster

The Plan, as Foster describes it, is a manual.

“It’s not a thick manual. It’s not some encyclopedia to pitching. It’s not pixie dust. It’s a plan,” he says.

“It’s our plan.”

Adds Holmes: “Everyone sat in a room for three days and hashed out the plan. Everybody came to an agreement that ‘this is how we’re going to do it.’ Then the book was written.”

“Everyone” included any pitching coach, scout or coordinator employed by the Rockies at every level. Daryl Scott, formerly the club’s minor league pitching coordinator and currently its catching coordinator; Mark Wiley, who serves as the director of pitching operations for the Rockies; farm director Zach Wilson; and Doug Linton, currently the minor league pitching coordinator, all had ample input.

Foster is still able to rattle off a list of concerns identified by the group.

“The guys that we had at the major league level couldn’t control the running game, didn’t pitch with tempo, showed their emotions often, couldn’t plus-and-minus pitch – and many of them didn’t. [There] wasn’t enough variance and controlling the strike zone. Too many walks.

“[It was] recognition through observation, recognizing ‘Okay if this is what we’re going to have, then we’re going to have a problem. We need to figure out a plan together.’

“I think it was a critical moment in time for the mindset and culture of pitching at Coors Field,” he says.

For a franchise that had always held the theory “we can outslug you,” a new culture – of pitching – was born.

Says Holmes, who had success with the Rockies as a relief pitcher during the height of the Blake Street Bombers Era (1993-97), “That’s the moment it started – right there.”

But this shift in culture was far more than “Kum Ba Yah,” sunflower seeds and high-fives. There were strict specifics to the plan. While not a thick manual, it was still a manual. It had rules and instructions, guidelines as to how pitching was to be handled, from the type of pitcher the group believed could have success at Coors Field to the way he would be taught every step of the way, from draft or acquisition to stepping onto the mound at 20th and Blake.

“We’re going to have controls, and within these controls we’re going to teach and train from the bottom all the way up,” explains Foster. “We did it because we wanted to make sure that when guys got to the major leagues, even though there’s always development that will take place even at the major league level, they’re further in the development process with a plan.

“Those who fail to plan, plan to fail.”

Holmes, as any Rockies pitcher will tell you, is the tactical one. He can look at arm motion, stride, grip or release and detect the smallest imperfection – and then fix it. But there’s no denying he, and the organization in general, knows that a Rockies uniform fits best on a certain type of pitcher.

“[We wanted] to go after hard four-seam guys, good spin rates on curveballs, sliders, mechanically sound guys,” Holmes says. “Basically, it’s not like you’re pitching away from contact, but your stuff has less contact. You’re going to give up a [few] more home runs, but the ball is not going to be put in play as much.

“When you play in the biggest field in baseball, you try to eliminate the ball being put in play.”

Aug 18, 2017; Denver, CO, USA; Colorado Rockies relief pitcher Jake McGee (51) delivers a pitch in the seventh inning against the Milwaukee Brewers at Coors Field. Mandatory Credit: Ron Chenoy-USA TODAY Sports

While Holmes tirelessly studies and tinkers with the nuts and bolts of an effective Coors Field pitcher, Foster handles the mental aspect – perhaps even the spiritual aspect – of pitching for the Colorado Rockies.

“Foster is a very good speaker,” says staff ace Jon Gray. “Very motivational.”

Foster utilizes and explains what he calls the “Five E’s.”

“Encourage, because it’s tough.

“Engage, have a relationship, build a bridge, have a conduit between us and the player.

“Equip, [Holmes] does a lot of that with the things that he has in his study and his background and his training with an eye to see detail.

“We Empower them. We encourage them and then we free them up. Do what you do. We don’t say, ‘You must do it this way.’ You’re good at what you’re good at. Be great at what you’re great at.

“Then, we Edify them. We want them to hear us speaking highly of them, because it’s a very tough mental place to succeed.”

Like Holmes, Foster knows what he wants to see in every hurler within the organization.

“Mental toughness. Talent. Humble. All of them,” Foster says. “When you put a group as large as we have together, usually you have some really high egos in that group. What we have right now is a group of young, humble, hungry, mentally tough, talented pitchers.

“Again, credit goes to Jeff Bridich, the visionary.”

“Frankly, we’ve decided to invest more money into the process.” – Jeff Bridich

In December of 2000, just eight seasons into their existence, the Colorado Rockies and newly appointed general manager Dan O’Dowd made a move that excited fans almost as much as the birth of the team or its 1995 postseason appearance. In retrospect however, the move – or at least the results of it – may have crippled the organization for the next 15 seasons.

Having witnessed lackluster pitching for most of the franchise’s existence, O’Dowd aimed to fix the pitching problem with one fell swoop. His first big move as GM was to sign two of the top free agent pitchers on the market – two-time All-Star Denny Neagle, and Mike Hampton, who had finished second in Cy Young voting just two seasons prior. Neagle’s contract was for five years, $51 million. Hampton’s was even more monstrous, coming in at eight years, $121 million. At the time, it was the largest contract in baseball history. Hampton’s Rockies agreement is still the 76th largest in the history of sports.

Both pitchers were utterly disastrous.

Hampton lasted just two years in Colorado before being traded. His record was a paltry 21-28, while the 3.59 ERA he’d enjoyed over seven seasons in Houston, and the 3.14 ERA he saw with the Mets just before heading west, ballooned to 5.75 in Colorado.

The 33-year-old Neagle was arguably worse. Over three seasons and 65 starts, he won just 19 games (while losing 23). His ERA with the Rockies came in at 5.57. The off-field problems that ultimately ended his career as a major leaguer were even uglier than his numbers.

For the next 11 years, it seemed that the Hampton-Neagle experiment defined the Rockies’ approach to pitching. Either O’Dowd was forever gun shy of signing another marquee (see expensive) pitcher, perhaps buying into the concept that pitchers simply couldn’t pitch at altitude, or owner Dick Monfort was unwilling to take another big-money gamble on O’Dowd’s advice. It also didn’t help that the media, both locally and nationally, had developed a narrative that pitching in the thin, dry air of Colorado was a futile effort at best.

Regardless of the culprit, not a single highly touted free agent pitcher made his way to the Rockies clubhouse in the years that followed the Hampton and Neagle signings. Most hurlers were brought up from within. Even the best performers had serious shortcomings: Shawn Chacon, an All-Star in 2003 who went 2-16 over the next year and half before being traded; Aaron Cook, an All-Star in 2008 who is No. 2 on the franchise wins list but won double-digit games just twice in his 10 years in Colorado; Ubaldo Jimenez, an All-Star in 2010 traded away after a disappointing start to 2011. Others seemed to be journeymen just happy for the opportunity to earn a major league paycheck. Of those journeymen, only Jorge De La Rosa, the franchise wins leader with 86, had any sustained success, and even that was intermittent. Simply put, there is nothing special about the Rockies’ most accomplished pitchers.

Perhaps the greatest thing about Jeff Bridich, a Harvard grad who is now widely considered to be one of the brightest minds in baseball, is that he wasn’t around when the Rockies inked Hampton and Neagle. Or maybe more accurately, he was willing to forget.

Still, to most who have followed the Rockies over their 25 years, it’s difficult to comprehend the likes of Wade Davis and Bryan Shaw, two pitchers with no ties to the organization and presumably their pick of the litter, would actually venture anywhere near Colorado.

Mar 30, 2018; Phoenix, AZ, USA; Colorado Rockies relief pitcher Bryan Shaw (29) pitches against the Arizona Diamondbacks during the eighth inning at Chase Field. Mandatory Credit: Joe Camporeale-USA TODAY Sports

“There are a couple different reasons for that,” Bridich suggests. “One is that, most often, veteran players who are free agents and have a choice in where they want to go want to go play for a team that they feel like can win games, can get into the playoffs, and can challenge for a division title – can challenge for a NL title, can challenge for a World Series berth. That’s an important part of it.

“The second ingredient would be, frankly, we’ve decided to invest more money into the process.”

There it is. The almighty buck. The currency that makes the Yankees the Yankees, the Dodgers the Dodgers.

The Rockies the Rockies?

Bridich has committed roughly $51.16 million of the Rockies’ estimated $140.76 million 2018 active payroll to pitching, according to figures on the salary tracking website spotrac.com. $30.5 million of that is going to three free agent relievers, Davis, Shaw and Jake McGee.

“A hard to sell to Dick?” Bridich asks, rephrasing the question he’s just been asked. “Not really.”

He continues.

“We’re pretty connected in the front office, too. Dick is very interested and involved, and he’s certainly connected to the team. He’s connected to the payroll, connected to our development process. He’s connected to the baseball piece. If you look back four seasons ago, including this year, so 2015, our payroll was $95 million. This year, probably by the end of the year, we’re going to be pushing $140 million.

“There’s been growth there, payroll-wise, which is great. The organization is healthy, it’s doing well. There’s a general growth plan that’s in place, so we’re able to look at each other and say, ‘Okay how are we going to act on this?’

“I think it’s pretty obvious that we were pointed and aggressive from a relief pitching and catching perspective in free agency this year.”

It is counterintuitive. It is not the Rockies way.

Behind closed doors, however, it has become the Rockies way. One can assume – probably safely – that at some point not long after Bridich was handed the reins, a very pointed conversation took place in Dick Monfort’s office. The topic? Pitching, of course.

“There was part of the strategic decision at the time to say, ‘Okay. We’ve got to be able to take risks here – and be okay taking risks as it relates to pitching. Our risk tolerance has to change,’” says Bridich. “It’s not like in the past we had shied away from trying to bring pitchers here. The shift isn’t polar; it’s just that on the spectrum of what we need to do to create a healthy organization, to create a healthy major league team that is going to contend, we were going to need to be a little bit more okay with risk on the pitching side.”

“No one’s afraid to pitch at Coors anymore.” – Chad Bettis

So here they are, the 2018 Rockies. The Blake Street. . . Bumpers?

“We believe great pitching can pitch in an ice arena,” Steve Foster says, speaking for both himself and Darren Holmes. “Coors Field, The Ballpark in Arlington, Philadelphia, Cincinnati – we believe it.”

Adds Bridich: “I do believe we can pitch, and I do believe we will pitch well this year.”

The term “sophomore slump” is shrugged off in Scottsdale like it’s a silly notion. There’s an air of confidence that seeps from the rubber on the mound clear up to the purple button atop a Rockies cap. It’s the kind of confidence that’s born of preparation, but also of simply not knowing not to be confident. Youth is bold and brash. Reliever Mike Dunn is the oldest member of the team’s pitching staff; he turns 33 in May. There are only six Rockies pitchers older than 30, all of them relievers.

Just down the hall from Bud Black’s office is a theatre where Foster is addressing the 30 pitchers invited to the major league camp.

“Anyone with 10 years of [MLB] experience stand up,” he bellows.

Holmes and Wiley stand up; both occupy places on the org chart, not the roster.

“Six years or more. . .”

Davis and Shaw stand up.

“Three years of experience or more. . .”

Another three or four stand.

“Two years?”

Four more stand; the rest remain seated.

“I always heard that [it was tough to pitch in Colorado], but I cannot tell you,” says 25-year-old Carlos Estévez, who enters his third season as a major leaguer. “I’d never been in the big leagues. I don’t know how it is with other teams. For me, this is how it is everywhere. This is the baseball that I’m supposed to pitch, and this is how I’ve got to perform. It is only this, because I’ve only been here and it’s all I know.”

The 2017 performance of the Rockies’ young staff was nearly unimaginable. From rookies Kyle Freeland, German Marquez, Antonio Senzatela and Jeff Hoffman, the Rockies were the beneficiaries of 93 starts and 38 wins.

“I think they were trying to outdo one another,” says No. 1 starter Jon Gray, “and none of them are scared and go fire it against the best teams.”

Gray, Chad Bettis, the eldest Rockies starter at age 28, and third-year man Tyler Anderson all experienced ample time on the DL last season. With their healthy return, it’s quite possible that one or more young starters from last season will begin, or eventually contribute, in the bullpen.

“There are no spots that are legitimately locked down,” says Freeland. “So everyone is chomping at the bit to get their spot and get their shot, and doing everything they can to be the best that they can be. That’s creating competition between all of us, and that’s only going to make us better as pitchers and as a pitching staff as a whole.”

Tough decisions lie ahead for Black, Holmes and Foster.

“This is the maybe the best depth this organization has ever had. By far,” says Holmes. “But whenever you look at other organizations like the Yankees, Houston – top-tier organizations – this is what they have.”

Says Foster: “The higher the flag is on the flagpole, the stronger the wind blows. Reality is that this is the major leagues. We’re trying to make a major league team.”

The vibe surrounding the Rockies this season is big league. Many times the laughing stock of the majors, the Rockies indisputably have a big league payroll, a big league skipper, big league hitters, big league starters and big league relievers.

“It feels like it’s different,” says McGee. “Last year when Bud got here it was a whole different mindset, and everyone bought into it.”

A few lockers down, Bettis says what every Rockies player and fan wants to hear:

“No one’s afraid to pitch at Coors anymore.”

After 25 years of Colorado Rockies baseball, it’s a very strange notion to grasp. Had anyone previously offered such a suggestion, it would have been dismissed as balderdash, rah-rah stuff from the clubhouse, “coach speak” – or worse yet, a downright lie. This season, while Bettis and others say it, the presence of Davis and Shaw – at least to some degree – proves it.

But baseball is an old, old game. And in its history, the only statements that matter are the those spoken at the end of the season. What the Rockies did last year, or what they say in Scottsdale, are of little importance.

“You look at the teams that win, go right to the team’s pitching statistics,” says Bud Black, who won a World Series as a pitcher with the Kansas City Royals in 1985. “You see the Dodgers, Nationals – last year, the Diamondbacks.

“The teams that win pitch well.

“For us to win, we’ve got to pitch well.”

Can the Rockies really – finally – pitch?

Wade Davis certainly thinks so.

Mar 31, 2018; Phoenix, AZ, USA; Colorado Rockies relief pitcher Wade Davis (71) pitches against the Arizona Diamondbacks during the ninth inning at Chase Field. Mandatory Credit: Joe Camporeale-USA TODAY Sports