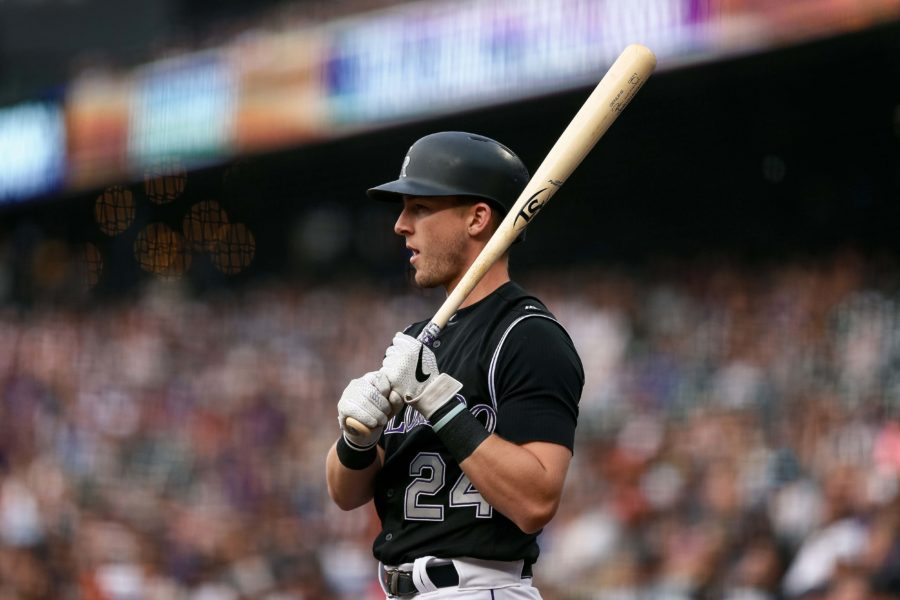

The day begins at noon for Ryan McMahon.

After pulling into the designated lot for Rockies’ players, he enters his second home. He grabs a coffee, then some lunch before the true work begins.

Video sessions, batting cage stints and talks with coaches encompass the remainder of his pre-game routine. But between it all, there’s a wrinkle: Candy Crush Saga.

In a quest to find a relaxation tool, McMahon began playing the game on his phone. Now, he’s making an impact for the Rockies, with his routine playing a large role.

Created in 2012, the game has 71 million likes on Facebook – it’s original platform – alone. The game is simple. Swipe candy in various directions to create sequences with the pieces around it. Once you’ve created a line of three-or-more identical pieces, they disappear, leaving room for new ones to enter.

In total, the game has an ever-growing amount of levels that currently sits at over 3,500. That apex is still a far one to reach for the Rockies’ second baseman.

“I’ve jumped up like 1,100 levels this season,” McMahon said.

The activity is not a new one to McMahon, rather, it’s a newly-refound platform. On a team bus earlier in the year, Mark Reynolds’ phone caught the eye of McMahon. After finding out that the veteran was playing Candy Crush – he was hooked once again.

“Reynolds was doing it on the bus and I was like ‘what level are you on?’ And said ‘well, I can get there.’ Ever since that, I’ve been playing it,” McMahon said.

Now, it’s a daily exercise. In the hour, give or take, that McMahon has before batting practice, he can be found at his locker. When he’s not talking to teammates, he’s ‘crushing candy’.

The trend of finding relief isn’t a new one. In his earlier years, it was another game with fewer pieces of candy.

“I used to play Words With Friends and things that like with my mom and grandma and family members,” McMahon said. “I’ve always had a little something.”

It’s about more than just messing around on his phone. McMahon, embarking on a journey to make an impact at the big-league level, is soothing his mind.

The lesson to find time for peace, however, is one that the aforementioned Reynolds has preached to the younger players.

“Guys listen to music and play cards, guys (are) on their phones,” Reynolds said. “You have to find things to do that will keep you sane. I don’t think the average person understands what we do daily and what we go through.”

In his attempts to ease the minds of teammates, Reynolds will even hand a younger player – like Pat Valaika on several occasions – a crossword puzzle. The game is simple. With two identical crosswords, the two players will race.

Similar to McMahon’s mission to pass Reynolds in Candy Crush, the competition is something that doesn’t simply end when the players exit the field.

“It’s what we do by nature,” Reynolds said. “We’re competitors. We compete at the highest level and even something as dumb as a crossword puzzle or Candy Crush or cards on the plane. You gotta stay competitive.”

Overcoming various obstacles, including competitors, has become second nature for McMahon. A change in position in the minor leagues and a utility role with sparing at-bats last year couldn’t stop him.

An inability to go through his full routine fails to affect McMahon either. Once that preparation – in whatever form it takes – gives way to an actual contest, there’s no longer a need for various coping mechanisms.

“Once you get out there, you’ve played this game so long that (the field) is my comfort zone,” McMahon said. “Standing out there with a bat or waiting for a ground ball, it feels comfortable to me. There’s never anything to stress about.”

A missed groundball or failure to come through at the plate is simply part of the game. In an effort to overcome the miscues that can occur in a game, McMahon enacts his only routine left.

In the jog out to the field or back into the dugout, the page is turned. Those briskly moving steps allow the third-year player to move on, something he was taught by his father.

“My Dad always preached to me that there (are) two parts to this game,” McMahon said. There’s an offensive side and a defensive side. You can’t let the offensive side affect the defensive side and vice versa.”

In all, McMahon spends nearly 12 hours in one day at the ballpark. Putting the sport into perspective – above all else – is the final route worth taking.

“At the end of the day, this really is just a game,” McMahon said. “You have your family, there are other things that are important. Obviously, this is really important to all of us, so you come here and give it your time but when you’re done with it, you’ve got to step away.”

The next day, it starts all over again.