This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition.

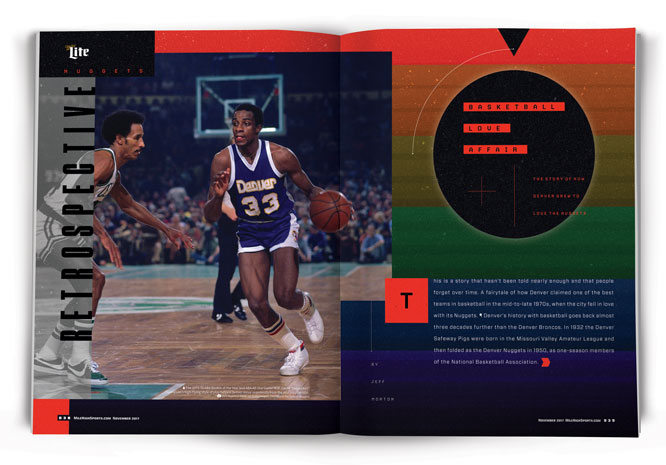

This is a story that hasn’t been told nearly enough and that people forget over time. A fairytale of how Denver claimed one of the best teams in basketball in the mid-to-late 1970s, when the city fell in love with its Nuggets.

Denver’s history with basketball goes back almost three decades further than the Denver Broncos. In 1932 the Denver Safeway Pigs were born in the Missouri Valley Amateur League and then folded as the Denver Nuggets in 1950, as one-season members of the National Basketball Association.

The early Denver Nuggets paved way for the ABA’s Denver Rockets 16 years later in 1967. While some would revise history and tell you that the Broncos were the first successful professional franchise in Denver as of 1977, you’ll be given permission to tell them that is false. The 1974 to 1976 Nuggets came closer than any subsequent Nuggets team to tasting championship glory. It was arguably the best Nuggets squad ever assembled.

This is the story of how Denver came to love the Nuggets.

***

1974-76: The Rise

“Before the Broncos were popular in 1977, the Denver Nuggets owned the city of Denver. I grew up in New York and I knew of the Nuggets long before I was aware of the Broncos.”

– Denver radio legend Sandy Clough

In 1974, the up and down, perpetually financially strapped ABA’s Denver Rockets needed a big change. While the purpose was to engage in a sort of “re-brand” – to use more modern terminology – the team also needed a facelift after seven years of some highs and many lows. The memory of rookie phenom Spencer Haywood leaving the Rockets in a contract dispute in 1970 (including charges of racism against first Nuggets owner Bill Ringsby by Haywood) for the NBA’s Seattle SuperSonics still rankled fans.

With the franchise under new ownership as of 1974, a contest was held to choose the new name for the team. Talks of an NBA/ABA merger had been going on for years and the NBA already had a team with the name Rockets in Houston. It was decided that the name Nuggets should adorn the uniforms of Denver’s ABA team to honor those Nuggets teams of the ’30s and ’40s. With a new name came a new life, new approach, and (most importantly) new players. The professional basketball scene in Denver was about to change in a big way.

The Nuggets’ facelift was consolidated by the new ownership and a new team president and general manager. His name was Carl Scheer and he would become one of the pivotal figures in Nuggets and indeed NBA/ABA history. Scheer was the creator of the Slam Dunk Contest and the man whose marketing model the NBA would use to great effect in the Larry Bird and Magic Johnson 1980s.

The well-known organization-builder was persuaded to come to Denver from the ABA’s Carolina Cougars (who were relocating to St. Louis) for the opportunity to become part-owner and team president. Scheer knew exactly who he wanted to bring with him to coach the team – Carolina assistant coach and former Rockets guard and all-time assists leader in the ABA, Larry Brown. With Brown came his fellow North Carolina Tar Heel and longtime friend Doug Moe. Brown and Moe would huddle together with Scheer to reinvent the Nuggets and change the course of the franchise. As Nuggets legend and Basketball Hall of Famer Dan Issel said: “Larry Brown was the best basketball teacher that I ever played for.”

Scheer had a plan to inject a combination of new players and, maybe more importantly from the fans’ perspective, fun. This required an infusion of talent that the previous years’ Denver Rockets did not have. Scheer aggressively pursued NBA-level talent, luring them to the renegade ABA. It began with Scheer, Brown and Moe using their contacts within the ACC – specifically with North Carolina and coach Dean Smith – to lure 6-foot-10 super-defender, Bobby Jones. The Houston Rockets had drafted Jones, but Scheer and Brown worked their magic to persuade him to come west.

Adding to the existing roster, which featured franchise stalwarts Byron Beck, Dave Robisch and Ralph Simpson, Scheer and Brown brought guard Mack Calvin with them, who was coming off an ABA All-Star season with the Carolina Cougars. Calvin added a point guard who could control the action and run the show, which Brown dubbed “the passing game.”

The 1974-75 Nuggets were up-tempo, free-wheeling, fun and electrifying. It showed in the attendance at the old Auditorium Arena downtown (currently known as the Temple Hoyne Buell Theater). A sterling and franchise-best record of 65-19 was by far the best in all of professional basketball that season. It worked so well that the team set a professional basketball record of 40-2 at home, a mark that stood until 1986 when the Boston Celtics went 40-1 at home. The Nuggets led the ABA in attendance that season, selling out many of the 42 home games. The town that was obsessed with the NFL’s Broncos fell in love with their Nuggets.

Playing a pioneering style of fast-paced basketball and storming their way through the ABA that season at a breathtaking pace, the Nuggets were led by Calvin and Simpson, the longtime Rockets player and All-Star. Suddenly, in one season, the Nuggets were the best team in the league. Playing a style that was light-years ahead, even in the free-wheeling ABA, the Nuggets exhausted their opponents and scored at a blazing rate.

Unfortunately this didn’t extend to the playoffs, as the Nuggets struggled to dispatch the Utah Stars in the first round. Then, playing the George McGinnis-led Indiana Pacers in the semifinals, the titular best team in basketball, the Nuggets, lost in seven games. McGinnis provided the knockout blow as he scored 40 points in Game 7 at the Auditorium Arena in Denver. The Pacers would subsequently lose in the Finals to the Kentucky Colonels, who featured Artis Gilmore, Dan Issel and Louie Dampier.

Some members of the Colonels were surprised to be playing the Pacers in the ABA Finals, as their star power forward admitted.

“The Nuggets had the best record in basketball that year; I think we were mentally prepared to face them in the Finals,” Issel said.

He wasn’t the only one who was surprised. So was the city of Denver, but that disappointment was about to turn into the greatest single-season run in Nuggets history.

***

An Explosion

“I thought we’d survive in Denver, but I had no idea that we’d see the explosion of growth that this sport has had.”

– Carl Sheer on DenverStiffs.com

“In 1975 I was basically sold to the Baltimore Claws. I’ve heard a couple different amounts, anywhere from $350,000 to $500,000. I don’t know which one is accurate,” Issel said recently.

Issel (aka “The Horse”) recalls the genesis of his rather circuitous route to the Denver Nuggets. He never thought he would have to leave the state of Kentucky, let alone be sold.

Through four years at the University of Kentucky and five years with the Colonels, he felt well at home. Colonels owner John Y. Brown Jr. (owner of Kentucky Fried Chicken and later the Governor of Kentucky) had lost money in 1975 on the team, despite winning the ABA championship that season. Issel was shocked to learn he had been sold, but dutifully reported to Baltimore. What happened next is one of the crazier parts of the denouement of the ABA.

Former ABA Commissioner Dave DeBusschere had “given” Baltimore the former Memphis Sounds. The new owners, led by businessman David Cohen, intended to start in Baltimore with a bang and purchased Issel from the Colonels. Ten days after Brown announced that Issel had been sold, the Baltimore Claws still hadn’t paid Brown for the big Kentucky star. It turned out that the Claws couldn’t afford Issel, let alone an ABA franchise.

“Ten days later [Brown] still hadn’t received his money and was taking a pretty good licking in the Louisville media,” Issel remembered. “Next thing I knew, John Y. walks into my hotel room in Baltimore and says ‘If I can get you out of here will you say some nice things about me in the Louisville newspaper?’ And I said, ‘Deal.’”

The Denver Nuggets had been able to secure the services of 7-foot center Marvin Webster away from the NBA. Before he was able to suit up, Webster contracted hepatitis and wouldn’t be ready to play for a significant amount of time. Carl Scheer, needing a center and sensing an opportunity, contacted John Y. Brown Jr. and made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. It was pitched as a sale/trade, sending longtime Rockets/Nuggets player Dave Robisch to the Claws with Issel going to the Nuggets. Famously, Brown burst into the Baltimore Claws boardroom and announced that Issel had been sold to the Nuggets instead for the same price and dared Claws ownership to stop him. They couldn’t.

The Baltimore franchise folded after playing a handful of preseason games.

The Claws’ loss was, of course, the crafty Scheer’s – and his Nuggets’ – gain. It didn’t stop there, however. In addition to pulling the highly rated Webster away from the NBA, the Nuggets pulled off possibly their greatest move in the summer of 1975: Managing to persuade highly coveted guard David Thompson to come to Denver instead of the Atlanta Hawks. (Both Webster and Thompson were drafted by the Hawks of the NBA.)

Thompson, the North Carolina State star, was known as “Skywalker.” Standing a mere 6-foot-3-and-a-half, the explosive shooting guard was instantly the Nuggets’ best player. Thompson gave the Nuggets something that only the New York Nets and Julius Erving could boast: A true superstar. Skywalker had just won the NCAA title and his national exposure was enormous. Thompson’s high-flying dunks and spectacular drives would capture the imagination of Denver and the country. This was something that would serve them well when the time came to negotiate a deal for an NBA/ABA merger.

Bill Walton has described Skywalker as “Michael Jordan before Michael Jordan.” This sentiment has been echoed by many who both played with and against Thompson in college, the ABA and NBA.

“You knew from day one that David was going to be a special player.” Issel said, “If he didn’t have his problems later on, he would be mentioned as one of the greatest ever.”

In a move that would fill Nuggets fans young and old with nostalgia for years to come, Scheer insisted to KOA radio, the Nuggets’ flagship at the time, that they hire and install Al Albert as play-by-play voice of the team. Al, the younger brother of broadcasting legend Marv Albert, instantly became the voice of the Denver Nuggets. Rick Morton, who at the time was splitting shifts between the Rocky Mountain News mailroom and working at Greyhound, was listening, enraptured, on the radio.

“One day Al Albert came in to Greyhound to pick up a package,” Morton said. “It was like meeting a celebrity.”

The Auditorium Arena was deemed too small for the NBA and the Nuggets were rewarded with McNichols Sports Arena (a.k.a. Big Mac), which opened in time for the Nuggets 1975-76 season. The new arena was state-of-the-art and could (in theory) fit up to 19,000 people inside, depending on the fire marshall (official capacity just over 17,000). This shiny new arena, opened next door to the ever-expanding Mile High Stadium, would be the Nuggets’ home for the next 24 years.

Newcomers Issel and Thompson fit well with the passing game enlisted by Brown and Moe. It was a big part of the Nuggets’ success – something pioneered by Brown and, to a large extent, The Horse himself. In those days, professional basketball was dominated by slow big men. Issel had played center at the University of Kentucky and switched over to power forward when coupled with dominating center Artis Gilmore with the Colonels. Brown (largely due to the health of Marvin Webster) played Issel at center. As The Horse explained:

“I [shot from outside] kind of out of survival. There was no way I could bang inside at 6-foot-9 with the more physical centers in the league. To take them outside and to have them do something they weren’t comfortable with or accustomed to was kind of my way of surviving in the league.”

Moving Issel away from the traditional center position on the low block allowed for a tremendous amount of spacing. As the Nuggets raced out to a 19-5 record to start the year, it allowed Thompson’s explosive nature to take hold in a big way. Flying dunks, spectacular drives and a revelatory mid-range game gave the Nuggets something they could hang on a banner, on a billboard, in a commercial. Most importantly, it drew in the fans. Big Mac was sold out more often than not and Denver went crazy for its Nuggets.

Mid-way through the season the Nuggets played a team of ABA All-Stars in the first All-Star Game of the modern era. Nuggets fans packed into McNichols Arena and were witness to a spectacle that long outlived the ABA itself. Finalists Thompson and the Nets’ Julius Erving competed in a Slam Dunk Contest that would become the stuff of legend. Thompson pulled out an amazing 360-degree dunk with power, and it looked like he was on his way to winning – until Dr. J emerged and stole the show and the nation.

Dr. J grasped the ball and ran the full length of the court. The crowd gasped in unison as he stepped on the free-throw line and leapt through the air – afro blowing in the breeze – and completed the first-ever dunk from the free-throw line.

“It was game over,” Morton recalled. “Everyone loved David but that was… spectacular.”

Bobby Jones was on his way to becoming the so-called “Secretary of Defense.” Often tasked with guarding the opposition’s best front-court player, Jones was the glue that held the Nuggets together. He was the best defensive player by far on a team that played fast and loose; aside from Jones’ defensive prowess, the mission was always to out-score rather than defend. Jones was invaluable to the Nuggets’ personality, as was the still-impressive Simpson as the Nuggets’ third-leading scorer. Chuck Williams held down the point guard slot after Calvin went to the Virginia Squires in the offseason. The starting unit was a well-oiled machine. This propelled the Nuggets to an ABA-best 60-24 record in the 1975-76 season.

Led by Thompson, Issel and Simpson in scoring, and Jones on defense, the Nuggets stormed into the ABA playoffs on a high. In a bit of irony, the Nuggets faced Issel’s old Kentucky Colonels with dominating big man Gilmore and most of the roster from their championship the year before. This became a knock-down, drag-out, seven-game semifinals series that some have described as the one of the great moments in Nuggets franchise history.

The series began with Game 1 at Big Mac on April 15, 1976. Before the first buzzer even sounded there was a problem – a big one. There was a malfunction in the electronic shot clock and it wasn’t working at all, nor could it be fixed in time for the game. ABA officials decided to play the game anyway. The PA announcer counted down when the shot clock reached five seconds; a crude air horn was used to signal the end of the clock and quarters.

This would prove fateful at the end of the game.

With three seconds left, the Nuggets were up three after Williams made one of two free-throws. The ball made its way to Dampier, the Colonels guard, who managed to get what he thought was the game-tying 3-point shot as time expired according to the PA announcer. Only, it wasn’t. Officials ruled that Dampier didn’t get the shot off in time. A furious Colonels coach Hubie Brown stormed the court in protest, screaming at the referees as they left the court. He felt Dampier’s shot was clearly good before the air horn sounded. To no avail.

The Colonels protested and were denied by the ABA Commissioner’s office, but league officials did assess the Nuggets a fine for the problems that led to the shot clock malfunction. This set the table for what would be an increasingly contentions series. Issel explained, “It was a difficult series, and I do remember it being very physical. Especially with me having to guard Artis Gilmore for the series.”

Kentucky channeled its frustration into a blowout win in Game 2. The series then went back and forth as the Nuggets and Colonels exchanged two-game winning streaks. After the Nuggets lost in a close Game 6, both coaches took shots at each other in the media – which included Hubie Brown calling Larry Brown a “crybaby.” Tensions were high going into Game 7.

Denver showed its love for the Nuggets in a big way. It was the hottest ticket in town. An ABA record 18,821 people (over-)filled Big Mac, all decked in blue and white, making what Morton described as “a huge, building roar” as he listened to Albert’s call on the radio.

“This crowd and this game will be a credit to our league. I compliment the people of Denver and their outstanding demonstration of civic pride,” Brown stated before the game.

The Nuggets left little doubt as they pulled away in the second half. Thompson was his Skywalker self, breaking out from middling games most of the series to score 40 points and pull down 10 rebounds. Issel also broke out with 24 points and 12 rebounds; he and an underappreciated Webster held Gilmore to 17 points, making the star center a non-factor. The best team in the ABA had crushed the defending champs.

The euphoria was enormous. Brown and his assistant coaches (including Moe) tearfully embraced on the sideline.

Issel recalled: “It was particularly satisfying to get that series victory against my former team.”

Morton – husband with a pregnant wife and working two jobs – leapt up and down in a nearly deserted Greyhound bus station as Albert called the final buzzer. Fans of all shapes and sizes celebrated in the city as the Nuggets became the first ever professional sports team to reach a championship series.

It was on to the next round and the last-ever series in ABA history – one that would go down as the best way to send out the renegade league.

***

Go with the Nuggets

“Oooo we’re gonna go with the Nuggets.

Hit that shot!

Score with the Nuggets tonight!”

– Suzanne Nelson and Craig Donaldson, “Go with the Nuggets” (1976)

In 1970, legendary NBA point guard Oscar Robertson filed an antitrust lawsuit against the NBA to block any potential merger between the NBA and ABA. Six years later the lawsuit looked like it was nearing some sort of settlement.

Unbeknownst to the rest of the ABA, Scheer and New York Nets owner Roy Boe had negotiated an exit from the ABA into the NBA before the start of the 1975-76 season, pending conclusion of the Robertson lawsuit. They unsuccessfully lobbied Kentucky Colonels owner John Y. Brown Jr., who was still loyal to the ABA, to join them in their attempt to join the senior league. The Nuggets and Nets by that time were by far the most financially stable and successful franchises in the league. After the rest of the league got wind of what was going on, a court order was filed to keep the Nuggets and Nets in the ABA for another season.

The financial peril in which the league sat was exposed that offseason as four teams folded either before the season began or just as it was starting. Memphis/Baltimore collapsed after three preseason games. The San Diego Sails and Utah Stars both folded midseason. The Virginia Squires, a former ABA stalwart, had to cave into financial realities. While they made it through the 1975-76 season, they were disbanded in May of 1976.

The merger of teams into the NBA was inevitable, as negotiations between the two leagues dated back as far as 1970. However, the resentment toward the Nuggets and Nets was palpable. The remaining seven teams applied independently to merge with the NBA, led by ABA Commissioner Dave DeBusschere. It was clear by the end of the season that the league was about to be no more.

It was against this backdrop that the two teams that tried to jump ship to the NBA before the season began met in the last-ever ABA Finals, the most-remembered and yet least-seen ABA Finals (the series was broadcast regionally, not nationally).

“I vividly remember watching every game of that ’76 ABA Finals in the basement of my college dorm in New York,” Sandy Clough remembered. “To me, the ABA teams – the Nuggets with Larry Brown, Doug Moe, David Thompson and Dan Issel – played like the Knicks did in the early 1970s, as opposed to the NBA, which by midway through that decade had become stale, boring and old.”

The Nuggets had become a national story with stars Thompson, Issel and even Simpson leading the way. The city of Denver certainly bought in, as the inevitable NBA merger was on the horizon – Nuggets Mania was at a fever pitch. Scheer brought temporary bleachers to Big Mac for Game 1, raising the capacity and ultimately reaching a McNichols attendance record of 19,034. Denver was ready for its first-ever trip to a championship series for a professional team.

“I couldn’t afford tickets and I was working two jobs, but Al Albert was my lifeline. We would huddle around the radio at the Rocky Mountain News and Greyhound. People couldn’t or wouldn’t do their jobs!” Morton recalled with a laugh. “We were all waiting for another ‘Issel missile’ or ‘Thompson with a rocket from downtown.’”

Game 1 of the ABA Finals was a tense, back-and-forth affair. The notoriously raucous Denver fans vibrated Big Mac with noise every time Thompson or Simpson would drive the lane, as if they expected something big to happen every moment. Conversely, the best player on the floor and arguably the basketball world, Dr. J, amazed the partisan Nuggets crowd with a scoring explosion, keeping the Nets in the game by sheer will.

For all the accolades that Game 6 gets in the annals of misty-eyed ABA remembrances, it is Game 1 that should be lifted up. Dr. J finished with 45 points and scored 18 in the fourth quarter. Tied at 118 with almost no time on the clock, Erving made a long two from the corner to beat the Nuggets with the clock showing zeroes, and he did so with Bobby Jones on him like a rented suit. Erving took over, and over the course of the subsequent six games cemented his legacy as the greatest ABA player; 19,000 fans were crestfallen.

“We lost Game 1; we had home court advantage, and Julius had 18 points in the fourth quarter,” Issel recalls. “That was going against Bobby Jones, who was arguably the best defensive forward in basketball at the time.”

What should be really memorable for Nuggets fans, however, is the tremendous fan response in the following game. In Game 2, the Nuggets bounced back and beat the Nets 127-121. The Nuggets had four players score 24 or 25 points and overcame a ridiculous 48 points from Dr. J. Scheer managed to squeeze in roughly 100 more fans than Game 1 into Big Mac before the fire marshall put a stop to it. The fans in Denver showed up better than anyone in ABA history for two games in a row.

The Nuggets and Nets were tied at one game apiece as the series shifted back to New York. While the Nuggets remained confident, the loss of home-court advantage loomed large as the Nuggets dropped games three and four in close affairs in New York. Thompson and Issel led the way in scoring both games, but Erving was dominant at home. The Nuggets would pull close but couldn’t quite get over the hump with the Nets pulling away down the stretch in both games.

The series returned to Denver in a must-win game for the Nuggets. The fans responded again by packing nearly 19,000 into McNichols as the Nuggets faced a do-or-die challenge down 3-1 in their series. Behind a 42-point third-quarter explosion, the Nuggets coasted to a 118-110 victory, sending the series back to New York for what became the most iconic game in the ABA’s nine-year history.

Coming out of Game 5, Thompson was facing criticism for what some regarded as a poor showing in the playoffs. While Thompson had his “Skywalker” moments, they weren’t as consistent as they’d been in the regular season; the Nuggets’ rookie ABA All-Star guard was struggling against the physical defense of Nets All-Star John Williamson. He hadn’t lost the confidence of their other star player Issel, however, who recalled: “Not only was David athletic, but he was a great basketball player without that athleticism. He didn’t have to get to the rim and dunk to score. He could score in any number of ways.”

Entering Game 6, Thompson had really yet to show the explosive potential that amazed the country for the regular season and in college at North Carolina State. This would change after the opening tip in New York, as Thompson would emerge from a series-low 19 points in Game 5 to play the single best game of his playoff career.

Thompson was aggressive, attacking the basket from the start of the game as the Nuggets built a small lead in the first quarter. They began to expand that lead in the second quarter, keeping up the pressure, double-teaming the heretofore unstoppable Erving. The Nets had trouble finding their offensive footing as Thompson and Issel stepped up on the scoring end for the Nuggets. The Nuggets’ most consistent offensive player in the series, Simpson, couldn’t get on track.

With two minutes remaining in the third quarter, on the backs of Issel (who finished with 30 points and 20 rebounds) and Thompson, the Nuggets built a 22-point lead at 80-58. It looked as if the series was headed back to Denver for Game 7

And then the roof caved in.

The Nets switched Erving on Thompson, allowing Williamson and others to freelance, essentially shutting down the rookie in the fourth quarter. Erving (who “only” scored 31 points in Game 6) eventually exploited the Nuggets on defense with his superstar patience, taking the first-half double-teams and turning them into points for his teammates.

According to Issel, the officials also let the Nets get away with increased physical play: “What I remember the most about Game 6 was how physical it was. John Williamson just started beating people up and the officials let him get away with it.”

The physical play and Dr. J’s decision to act as facilitator opened up Williamson to score 28 points, most of them in the fourth quarter. The Nets swallowed up the Nuggets in the fourth and catapulted themselves into basketball lore by defeating Denver 112-106 in the last-ever ABA game.

What a way to go out.

***

One wonders how different things would be in the Mile High City if the Nuggets had managed to win that last ABA Finals. Nuggets Mania had ramped to a fever pitch by the time the league merger was approved in June of 1976. The Nuggets had spent the previous two seasons being the best team in all of professional basketball, NBA included, only to fall short when it came to the playoffs.

The ABA had an enormous effect on the stodgy, old, boring NBA, an influence that would be felt even until the modern age. The Nuggets use of “pace and space” with Brown and Moe (an extension of offenses run by Smith at North Carolina) can be seen in every single modern-day team. The 3-point line, along with the wide-open, free-wheeling, athletically fueled games in modern basketball, were direct byproducts of the renegade league with zany characters like Spirits of St. Louis’ Marvin Barnes and Nuggets’ trainer extraordinaire Robert “Chopper” Travaglini. There is a whiff of misty-eyed nostalgia there, and things weren’t always that good, but the legacy remains.

The story of the best-ever and most-talented Nuggets team doesn’t end there. The franchise entered the NBA the very next season along with the Indiana Pacers, San Antonio Spurs and New York Nets. The Nuggets continued to leave their mark on the NBA after they became a part of it, with local fans playing a big part in Denver’s reputation as, yes, a basketball town in the mid to late 1970s.

That, is a story for another time. The Nuggets would show that they not only belonged in the NBA, but that they could win and win big. Thompson’s electrifying, gravity-defying style of play became a national phenomenon.

As Morton recalled, “Those were the best years. Everyone in Denver loved the Nuggets. Everyone was excited for the next game and to read about it in the paper. I know; I was there at the Rocky Mountain News printing out the daily paper. People would ask about those Nuggets and hang with every loss and celebrate with every win.

“It was truly when the Nuggets ruled Denver.”