This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition.

“Light shall shine out of darkness.” – 2 Corinthians 4:6

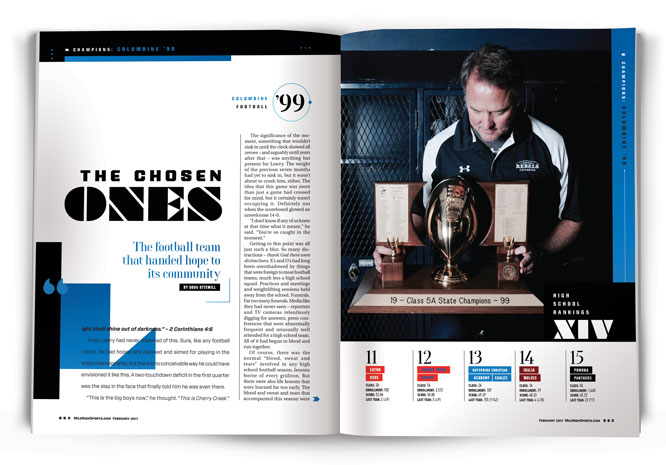

Andy Lowry had never dreamed of this. Sure, like any football coach, he had hoped and planned and aimed for playing in the state championship, but there’s no conceivable way he could have envisioned it like this. A two-touchdown deficit in the first quarter was the slap in the face that finally told him he was even there.

“This is the big boys now,” he thought. “This is Cherry Creek.”

The significance of the moment, something that wouldn’t sink in until the clock showed all zeroes – and arguably until years after that – was anything but present for Lowry. The weight of the previous seven months had yet to sink in, but it wasn’t about to crush him, either. The idea that this game was more than just a game had crossed his mind, but it certainly wasn’t occupying it. Definitely not when the scoreboard glowed an unwelcome 14-0.

“I don’t know if any of us knew at that time what it meant,” he said. “You’re so caught in the moment.”

Getting to this point was all just such a blur. So many distractions – thank God there were distractions. X’s and O’s had long been overshadowed by things that were foreign to most football teams, much less a high school squad. Practices and meetings and weightlifting sessions held away from the school. Funerals. Far too many funerals. Media like they had never seen – reporters and TV cameras relentlessly digging for answers, press conferences that were abnormally frequent and unusually well attended for a high school team. All of it had begun to blend and run together.

Of course, there was the normal “blood, sweat and tears” involved in any high school football season, lessons borne of every gridiron. But there were also life lessons that were learned far too early. The blood and sweat and tears that accompanied this season were new and inexplicable, most thought insurmountable. Blood that no 16-year-old kid should ever have to see. Sweat that soaked the navy and silver of the Columbine Rebels like no other team in the state. And tears. So many tears! Tears that flowed daily. Tears that hurt and tears that healed. Tears that were more justified than welcome.

“I can’t tell you that I remember on a daily basis how we did it,” Lowry would later say. “We just did it together.”

When that clock at Cherry Creek’s Stutler Bowl finally and mercifully struck zero, the score beneath it read what the entire nation wanted it to read: Columbine 21, Cherry Creek 14.

At that moment, Frank DeAngelis turned from the sidelines and looked up into the bleachers.

“They were filled, and people were crying and chanting, ‘We are Columbine!’ It’s something I’ll always remember,” DeAngelis said. “All I could think about was that as this community continues to heal, we’re going to need this.

“When I looked up there, I did not only see cheerleaders or poms or people and parents who supported athletics. I saw community members. I saw kids that may have never before attended a football game during their time at Columbine. And we came together. We are Columbine.

“And the football team represented the resolve of the Columbine school community.”

***

On April 22, 1999, just two days after the deadliest high school shooting in U.S. history, Andy Lowry strolled through Clement Park, a span of grassy fields that were beginning to sprout bright green grass less than 1,000 feet from the spot where Lowry had encountered a victim who had been shot twice, once in the leg and once in the neck. His path was strewn with flowers and makeshift memorials honoring those who had just been killed at nearby Columbine High School. Lowry walked with Bishop Walker Nickless, who was the assistant pastor at St. Bernadette’s when young Andy was in 8th grade; Bishop Nickless was also the priest for the weddings of Andy, his brother and his two sisters. At the end of their conversation, the Bishop stopped, looked Lowry squarely in the eye, and told him something he’d never forget.

“You know, Andy, God put you here for a reason. It’s not an accident that you’re here.”

The words hit the coach like a ton of bricks, the weight stacked squarely on his shoulders. He carried that with him everywhere, for 10 years at least.

“Wow, he thought,” he thought. “I’m not sure how to handle that.”

Boldly, he accepted the responsibly bestowed upon him. He prayed, regularly asking God for guidance. And he was strong. But he wasn’t alone.

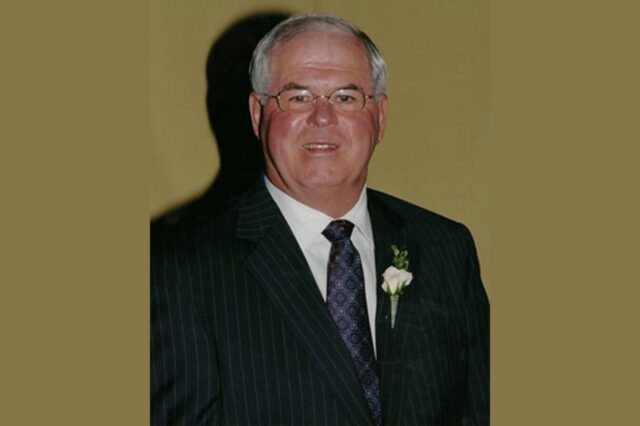

DeAngelis, Columbine’s principal for 18 years, including the ’98-99 school year, and the man who hired Lowry in the spring of ’94, also felt the weight tied to the responsibility, and maybe even the “survivor’s guilt” of guiding his school and community through tragedy.

On the day of the shooting, DeAngelis was notified that there had been gunfire in the school. He thought it was a senior prank, but headed into the hallway en route to the area where the noises were heard. Not far from his office, he encountered the gunmen face to face.

“I should have died that day,” he said. “I still remember vividly glass breaking behind me, the sound of gunfire – and I’m thinking, ‘This is it.’

“But things happened that day that you just can’t explain.”

One of those things DeAngelis attributes only to his faith. As he ran from the gunmen, he noticed a group of girls coming out of a P.E. class; unbeknownst to them, they were headed right for the hallway where shots were occurring. DeAngelis’ instinct was to run toward the girls and redirect them to a safe place. That safe place was the gymnasium, but when he arrived the doors were locked.

As the gun blasts grew louder, DeAngelis knew it wouldn’t be long before he again encountered the gunmen. Standing in front of a locked door, mere seconds likely to be the difference between life and death, he reached inside his suit pocket and fished for his keys. On this one key ring, however, there were 35 different keys. Miraculously, the lone key he grabbed – on the first try – was the key to the gym. He and the girls were saved.

Dave Sanders, a business teacher and girls basketball coach at Columbine, was not as fortunate. DeAngelis later learned that as the gunmen moved toward the gymnasium doors, they were distracted by Sanders as he tried to usher students up some nearby stairs. Rather than pursuing DeAngelis and the girls, one of them turned and shot Sanders. It might have been the split second necessary to unlock the gym and deliver the girls to safety.

Two days later, presumably around the same time Lowry strolled through Clement Park with Bishop Nickless, DeAngelis got a phone call from Father Ken Leone of the St. Frances Cabrini Parish, who insisted he pay a visit to the church that night. When DeAngelis arrived, it was packed with students and families from Columbine. They prayed, and when they were done, Father Leone leaned down and whispered something in DeAngelis’ ear.

“Frank,” he said, “you were spared on that day; you have no idea why. But now you need to go rebuild that community. It’s going to be tough, but you won’t have to take on the journey alone.”

The irony that Lowry had been told essentially the same thing on the same day by a different Monsignor from a different church was not lost on DeAngelis.

“It was so great that Andy and I were walking this path together,” DeAngelis said.

***

Still, rebuilding Columbine would be a monumental task. There was no replacing. No fixing. No undoing. The best that anyone could patiently hope for was to heal.

And football was still just football, a game that could in no way, shape or form make up for the losses of April 20. Andy Lowry knew that.

He even had a good team. His Rebels had narrowly missed going to the state final the year before and much of the roster remained intact. Looking back, Lowry is amazed that his team was not decimated by open enrollment. “They could have left,” he said. “And nobody would have blamed them.”

Lowry’s team fielded more than 100 players, including the likes of Dusty Hoffschneider, who would eventually be named the two-time Colorado defensive player of the year and win three state wrestling titles – Lowry called him “the rock that held his team together” – and Landon Jones, the monstrous, featured fullback in Lowry’s single wing offense who already had a Division I scholarship in hand.

It was missing Matt Kechter, a would-be junior who was killed in the shootings. The Rebels all wore No. 70 – Kechter’s number – on their practice jerseys to honor their fallen teammate.

The task for Lowry was the same as it was every year: Take a group of kids, find commonality and get them all pointed in the right direction. But in the summer of ’99 that figured to be tricky. Not only were Columbine’s facilities off limits, making summer lifting and 7-on-7 a challenge, but parents were seizing the break to get their kids out of Colorado and away from the horror they’d just witnessed. Besides, Lowry assumed the season would be anything but “normal.” This year was more about saving people than making football players.

But the opposite actually happened. Normal was what Columbine needed.

Right after the tragedy, it was hard for kids – and adults too, really – to go home. The only people who could truly understand and relate to Columbine were those who were there. It was tough, even for family members, to comprehend what those who were present felt and thought. But when those who were subject to ground zero were together, everyone could relate, everyone could talk. There was no better sanctuary than football practice.

“We needed to see each other’s faces and be around each other, just get our minds off of it,” said Lowry. “That was our home. That was our family. We had the ability to be able to recover with each other.”

Oddly, the one thing that posed the team’s biggest obstacle, was the very thing that provided the glue that all championship teams need. Lowry was used to searching for that one thing that brought his football teams together – the common thread that unified or solidified a team, that slice of conquered adversity that magically took teams from good to great. There was nothing more common, no stronger a bond, no steeper hill to climb, than being a part of Columbine on April 20.

On top of that, athletes at Columbine had become a target of blame. The suffocating steady dose of media wanted to point the finger at someone or something; they wanted to know why? So they drew overly simplified lines of division all over Columbine’s already shattered campus. Jocks versus outsiders. Bullies versus weaklings. Who better to represent the villain than a big, tough football player? Revered by the strong, hated by the weak.

“We were the ones being blamed,” said Jones, whose scholarship to the University of Colorado was mysteriously taken off the table the summer that followed the shootings. “We were guarded.”

Adult leaders like Lowry and his staff, like Principal DeAngelis, were guiding and protecting young people as best they could, but it worked both ways: “We needed each other,” said Lowry.

“I needed that school more than it needed me,” said DeAngelis.

When the season finally began, it did so with a 37-0, lightning-shortened drubbing of Denver East. The Rebels rolled to a 5-0 start, never winning by less than 14 and blanking two teams. With wins came intensified scrutiny from the media. The first loss came against Pomona, in what Jones later called a “blessing in disguise.” There was enough pressure to win, to help heal Columbine, but being “perfect” was even harder.

That sole blemish would later add to the mystique of the season, becoming an integral chapter in the story of the ’99 Rebels.

***

With only one loss heading into the state quarterfinals, Columbine squared off against Fairview, a formidable opponent that featured one of the state’s top running backs and indisputably its best quarterback, Craig Ochs.

Late in the game it appeared as if Columbine had finally met its match; a respectable season was about to come to an end.

“Fairview was hammering us,” Lowry said. “We were about done and all of a sudden…”

There was a late interception. There was one of the oddest onside kick recoveries in state history. Twenty-one unanswered points.

“…They just lost all the momentum. That was just kind of like a miracle – that was divine intervention.”

Columbine 21. Fairview 17. It was onto the semifinals where the Rebels made quick work of Ponderosa, whipping the Mustangs at their place 26-8.

Sitting at 12-1 and on the verge of winning the school’s and Lowry’s first-ever state championship in football, it didn’t go unnoticed that one more victory – the biggest one – would result in exactly one win for each victim in the Columbine shootings.

The football team had dedicated its season to Kechter, and there were plans to hand over the trophy – whichever one they received – to his younger brother, Adam. But a unified front of players, Lowry and DeAngelis all saw significance in 13 wins for 13 victims. Sure, Kechter was once in the trenches and he should have been there going toe-to-toe with Cherry Creek alongside them. But Sanders, Rachel Scott, Daniel Rohrbough, Kyle Velasquez, Steven Curnow, Cassie Bernall, Isaiah Shoels, Lauren Townsend, John Tomlin, Kelly Fleming, Daniel Mauser and Corey Depooter were all Rebels, too.

This was bigger than football.

“We felt like there was a greater power behind all of it,” Jones said. “There was something beyond what we were doing. It was almost destiny.”

Jones wept at halftime of the championship game. The Rebels were down and Cherry Creek was still the powerhouse that it had been throughout the ’90s. But those tears didn’t last long. Forget about destiny, Jones didn’t want to rely on that. He didn’t want to come up just short of the mission – 12 wouldn’t do.

“The resilience of those kids…” Lowry says now 17-plus years removed.

The rest is the storybook ending that the entire nation wanted. Adam Kechter hoisted the trophy. Chants of “We are Columbine!” echoed throughout the Stutler Bowl. Cherry Creek’s Mark Woolford made it a point to venture into Columbine’s locker room; addressing the team, saluting them on a toughness that stemmed from far more than just the title game. The Kechter family came in too. Everyone prayed. Everyone cried.

Lowry and Jones both recall an odd mix of jubilation, exhaustion and guilt. Should they be celebrating? This was a football game. It couldn’t replace those who had been lost. It couldn’t undo what had been done.

But it was a step. In retrospect, there’s no denying that what the Rebels did that season had great meaning. It meant something to everyone at Columbine. It would still be a long road to recovery – some still haven’t fully recovered and some never will – but perhaps the healing had begun for many.

“It’s easier for us for us to look back, knowing that God’s hand was with us all the way through in the recovery aspect of it,” said Lowry. “It was good to see people smile, because we were not able to do that prior to that game.

“Nothing was better than that.”