This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition.

I am a graduate from Valor Christian and would like to put in my two cents about my view from the inside.

That was the first line of a well-penned essay that appeared in the “comments” area of milehighsports.com. I say it was an “essay” because it was longer than the typical response that follows the typical sports column written on the site. These words were more thoughtful, too – not the standard popping off about the Broncos quarterback controversy or the Rockies pitching staff. Someone had taken the time to write this one.

The piece was offered in response to a column I’d written about Valor Christian High School titled “Loathed or Loved? Valor Christian is both.” I didn’t know who the writer was; the byline simply said “E.”

We – as in the “Royal We” – have been talking about Valor Christian High School since it opened its doors in 2007. Frankly, the school that rests upon the sprawling campus at 3775 Grace Boulevard in Highlands Ranch has been the subject of controversy since then, or perhaps more accurately, since Valor’s athletic teams began winning.

That’s when folks really started to take notice.

A Christian institution – wealthy, poor or somewhere in between – generally doesn’t garner much attention from the community at large, at least nothing out of the ordinary. But when that institution excels at sports, especially at an almost unprecedented level, all of a sudden “we” perk up. Add a substantial amount of resources on top of those wins and a place like Valor Christian quickly becomes a household name.

But what do we really know? We see from the outside. We read what others have written. In the case of Valor Christian, we’ve seen well-documented success in sports. In just eight and a half years of existence, the Eagles have won 15 state championships, six in football alone. Valor regularly finishes within the top 20 in this publication’s annual ranking of Colorado’s high school athletic programs (this year, they come in at No. 6).

But there have been blemishes along the way, too – most notably, accusations and reports of recruiting. According to the CHSAA, the governing body of high school sports in Colorado, Valor Christian received nine sanctions in its first four years, including four serious violations. In 2013, a Valor Christian assistant hockey coach sent a recruiting letter to coaches in Texas. When the school was notified of the letter, the coach was immediately let go.

Those are things we “know,” information that’s been heard or read. But what else do we know? What do we really know about the daily happenings at Valor Christian High School?

Here’s what I know in general: Few schools, if any, have never made mistakes with regard to their athletic program. Few titles, if any, have ever been won without hard work and dedication. I know that between the lines of competition kids are kids – all the other stuff doesn’t matter – and that sports can teach life lessons that nothing else can.

Those are truths that I know, beliefs I’ve come to form after years and years both competing in and observing sports. They have nothing to do with Valor Christian or any one school specific.

That’s what I know. But what do we truly know about Valor, or what it’s like to be a student or coach there?

E knows.

***

Hearing “Valor sucks” being yelled at you is nothing. It happens all the time and it’s nothing compared to the many things the school and its students have been through. I was involved with the Valor Sports Network, and one (home) game I had to video from where the opposing side’s parents sat. The whole time we were cursed and yelled at, and insulted…by the parents. They where yelling at us, saying that we are the “rich kid school” (I, along with many others, was on financial aid, so that made things awkward) and much more colorful things. Yet, because we were Valor, we couldn’t do or say anything about it because everything we do gets blown out of proportion. Keep in mind, we were 15.

The column I wrote that spurred E’s response was based on an event I’d witnessed personally. I was at Pepsi Center watching a Nuggets game, seated along the aisle; during a timeout a young man – let’s call him a sophomore – walked down the steps toward his seat. He was wearing a navy blue sweatshirt that said VALOR across the back. As he sauntered down the stairs, a voice from behind me – let’s call him an adult – shouted through cupped hands: “Valor sucks!”

The roles suddenly reversed. The “adult” just kept walking, paying no attention to the heckler behind him. The “kid” a few rows back giggled like he’d somehow just won a playground squabble.

A similar occurrence took place at the final home game of the Denver Broncos 2015 season. At halftime, the state championship football team from every level was honored. When 5A state champ Valor Christian was announced, a smattering of boos filled the stands at Sports Authority Field. Fans of the same team were suddenly divided. The same folks who were cheering for the home team were now jeering another Colorado team, one made up of high school students. Again, adults heckling kids. Something is wrong with this picture.

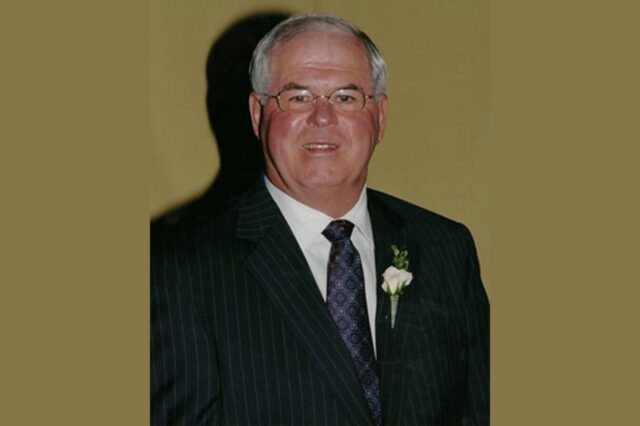

“Seriously?” Jamie Heiner, Valor Christian’s athletic director, asked when I texted him about his school’s reception. “We got booed?”

Seriously.

I’ve known Heiner for quite some time, long before he became the athletic director at Valor Christian. From what I knew prior to his time at Valor, he was both an athlete and a businessman. His prep days were spent as a multisport participant at Rocky Mountain High School in Fort Collins. In college, he starred at Northern Colorado where he was a two-time All-North Central Conference linebacker and an integral part of two NCAA Division II national championship teams. He was an Academic All-American in addition to earning All-American status his senior year. After college he got a shot at the pros, playing for the Tennessee Titans, Birmingham Thunderbolts (XFL), Amsterdam Admirals (NFL Europe) and the Colorado Crush of the AFL.

In 2005, he opened Impact Sports Performance, a training facility in Broomfield. It was a first-class set up where I witnessed, first-hand, Heiner helping kids of all ages and abilities become better athletes. He was a gentle giant, looking like he could still play in the NFL, but coaching like a soft-spoken grammar school teacher, always having a sense of humor and never taking sports too seriously. As far as I could tell, kids loved him. He pushed them, but knew how to pick them up as well.

And that’s probably why he was offered the job as head football coach at Cornerstone Christian Academy in 2010. That first season, his Bulldogs went 1-8. The next year they won the Metro North League. When they clinched the league title, Heiner was named the Denver Broncos High School Coach of the Week.

Not long after, he was offered the job as Valor Christian’s director of performance. And when Rod Sherman, the school’s only athletic director, stepped down in the spring of 2015, Heiner was surprised when he was asked if he might be interested in the position.

“Quite honestly, I’ve never considered being an A.D. in my life until there was an opportunity,” Heiner told the Denver Post in May of 2015.

Today, he’s Valor’s athletic director, but he’s still the same Jamie Heiner I’ve always known, rich in both values and faith, a fierce competitor but one who’s well-aware of the proverbial “bigger picture.” The foundation that makes up who he is, and the values he instills in his coaches and the student-athletes at Valor Christian, were born long ago. Long before he called himself a Valor Christian Eagle.

***

I don’t think people understand the pressure both the school and the students are under. We were one of the first two schools in the world to have ACSI Exemplary Accreditation status. Every single person in our school worked extremely hard with academics; the football team is not exempt from performing at a high academic level. I knew people who transferred from the school just so that they could get a higher GPA. My school was hard; I have less work and stress here in college than (I did) back at Valor. With the theater program there was no opportunity to do homework, practice ended at 10, only after that did you find the time. Also because we are a private school, anyone from anywhere can be enrolled. We had kids driving from Evergreen every day just to go to school there.

Rod Sherman’s football players play hard. They probably prepare even harder. Money can only buy the weights; they still have to be lifted. This year, and in six of the last seven years, the final standings suggested that Valor was the very best the state could offer. Make no mistake, every state champion works incredibly hard, no matter the advantages they may or may not have.

But I found it interesting that during the week before this year’s state football championships, Sherman sat in front of a room full of media and spoke about his, and his school’s, desire to see his football players do other things – to be well-rounded. It’s a tired, modern gripe, but anyone involved in youth sports is familiar with the complaint that the modern school boy (or girl) is forced to “specialize.” At Valor, Sherman told the gathered media, nothing could be further from the truth. Valor is relatively small in the context of 4A and 5A competition; having enough kids to compete, to some degree, actually requires athletes who are willing to play multiple sports. Furthermore, it requires a staff that cooperates with one another; they can’t be territorial or selfish.

Sherman talked about his roster filled with multi-sport athletes and made reference to one of his players who had a part in the school play. The seniors who were attending the press conference started chuckling; in low voices they cooed the word “Spooooooooon!”

In the next day’s Denver Post, columnist Mark Kiszla wrote a fantastic piece that explained what – or who – they were cooing about. It was Valor senior running back and linebacker Tanner “Spoon” Tadra, who earned the nickname “Spoon” because of his role in “Beauty and the Beast” – in which he played a “dancing spoon.”

Spoon had seven tackles and added 22 rushing yards in the state championship game. He’ll run track this spring.

The 2015 AP College Football Player of the Year and Valor alum Christian McCaffrey played three sports (football, basketball and track) for the Eagles throughout his entire prep career. McCaffrey was also a first-team Academic All-American at Stanford this past season.

It’s ironic that the same Coloradoans who hoped McCaffrey the Eagle would lose, were wholeheartedly rooting him on to win the Heisman Trophy as a Cardinal. McCaffrey didn’t learn work ethic and dedication after arriving at Stanford. Those are traits that were developed over the course of his life, from great parenting and presumably from his time at Valor Christian High School.

How is it that we can applaud the final product, but boo such a critical stage of the process?

***

For us the bar was raised, we were expected to do more and become more. We are not successful because of the famous name of one of our coaches or because our students pay tuition. But because of the high standard that was put on us. Part of our education problem in the U.S. is because nobody is being “pushed” (granted, Valor occasionally pushed too hard). Nobody could get extra credit and nobody turned assignments in late. “Easy A” classes didn’t exist at Valor, not even in the arts. Classes are intense, homework was more then just busywork (though there always was a lot of homework), and extracurricular activities are always competitive. Everything was expected to be hard.

We are a country that often questions our own toughness. We wonder whether or not every kid at field day should get a ribbon. We’re sometimes irritated by how politically correct everyone must speak or act, as if the possibility of insulting a single person is a valid reason to discontinue the pursuit of something right or good. Rather than having a potentially uncomfortable conversation, important topics are avoided all together.

It seems to me that those who run Valor Christian have simply taken a stance. They’re not wondering; they’ve already decided; they’re not afraid of the conversation. Unabashedly, they want to be tough, direct, intentional. But they also want to be kind and compassionate, teaching their athletes to win or lose with class and dignity. That’s not to say other schools, teams or coaches don’t have a similar approach. Many do. But it’s unquestionably a focus at Valor. At least that’s my read.

In my column, I wrote that we are a “win at all costs society.” In retrospect, that may have been too harsh. Some people are. Others are not. Most are somewhere in the middle, picking and choosing which battles are truly worth fighting. Still, we value winning. We are, by our very nature, competitive.

What’s wrong with a group of people collectively saying they’re going to strive for the very best – as scholars, as athletes, as philanthropists, as people? Whether it be in sports or school, isn’t that, to a degree, commendable? That notion only becomes wrong or corrupt if the pursuit is absolute and there are no boundaries, rules or scruples. But I don’t get that sense about Valor these days.

It’s been two years since Valor has had any CHSAA infractions. When is it time to move forward?

“We are certainly not perfect,” Heiner once told me. “In fact, we make mistakes all the time.

“But when people come on campus and get to know us, how intentional we are, see how hard we work both academically and athletically, but also culturally, and (they see) how how much time we invest into the spiritual health of our students and coaches, they typically come away with at least an appreciation, if not being super supportive.”

Here’s a guess: If you already don’t like Valor, Heiner’s words might come across as arrogant or martyred, as even he suggests, “look at us, we work harder,” or “poor us, we get persecuted for no reason.”

That’s not it at all. Heiner is a very normal guy. He’s not arrogant in any way, and for nearly every chapter of his life, he’s been on the other sideline. He played at a big, public school. He enjoyed college sports at the Division II level, an existence that doesn’t include the facilities that schools like Oregon, or now Colorado, enjoy. He’s extremely real. The resources he has now are nice – no question – but his personality, faith and toughness were forged long ago. Money can’t, and won’t, change that.

***

Every time I was asked what school I went to I was always hesitant to answer. (If I did), people I had been talking to and having fun with would then shut me out with a “F*** Valor.” High school students should not have to be afraid about whether or not they should wear a sweatshirt with the school’s name on it, or telling people what school they go to. Even during my time at college, I was told I couldn’t be friends with the guy I was talking to because he discovered that I went to Valor.

Hate, as our parents always told us, is a very strong word.

Hate should not be used to describe Valor Christian, or any team or school for that matter. If anything, it should only be used in the context of sports, as in “Broncos fans hate the Raiders.” Even then, a better word can be chosen.

Do we really hate Valor? No. Not really. Even Jamie Heiner knows this.

“I don’t think I know anyone who really hates us,” he says.

More likely, we don’t know or understand Valor Christian. We haven’t taken the time to fully examine why anyone would, or could, “hate” a school or its athletic program.

Maybe it’s time we did.

Read the other side: “Why we hate Valor Christian” by D-Mac