This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition.

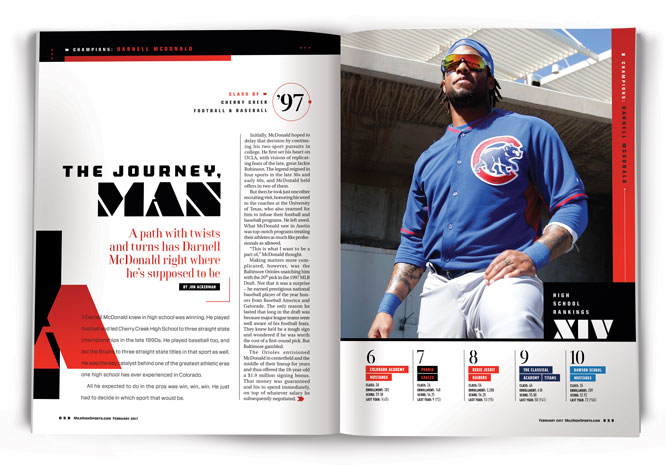

All Darnell McDonald knew in high school was winning. He played football and led Cherry Creek High School to three straight state championships in the late 1990s. He played baseball too, and led the Bruins to three straight state titles in that sport as well. He was the key catalyst behind one of the greatest athletic eras one high school has ever experienced in Colorado.

All he expected to do in the pros was win, win, win. He just had to decide in which sport that would be.

Initially, McDonald hoped to delay that decision by continuing his two-sport pursuits in college. He first set his heart on UCLA, with visions of replicating feats of the late, great Jackie Robinson. The legend reigned in four sports in the late 30s and early 40s, and McDonald held offers in two of them.

But then he took just one other recruiting visit, honoring his word to the coaches at the University of Texas, who also yearned for him to infuse their football and baseball programs. He left awed. What McDonald saw in Austin was top-notch programs treating their athletes as much like professionals as allowed.

“This is what I want to be a part of,” McDonald thought.

Making matters more complicated, however, was the Baltimore Orioles snatching him with the 26th pick in the 1997 MLB Draft. Not that it was a surprise – he earned prestigious national baseball player of the year honors from Baseball America and Gatorade. The only reason he lasted that long in the draft was because major league teams were well aware of his football feats. They knew he’d be a tough sign and wondered if he was worth the cost of a first-round pick. But Baltimore gambled.

The Orioles envisioned McDonald in centerfield and the middle of their lineup for years, and thus offered the 18-year-old a $1.9 million signing bonus. That money was guaranteed and his to spend immediately, on top of whatever salary he subsequently negotiated.

And so, two days away from two-a-days at Texas, McDonald made a $2 million choice that forever altered the course of his life. His next game came in the uniform of the Delmarva Shorebirds, the Class A affiliate of the Orioles. Instead of wearing the burnt orange of Texas and playing football in front of 75,000 people at Texas Memorial Stadium, he played baseball in the town of Salisbury, Md., with a population of less than 25,000.

“You look back like, ‘Ah man, you can’t pass up that type of money,’” says McDonald, now 38. “It’s tough to do that when you don’t really come from a whole lot of money and your family doesn’t have money. It’s tough to say, ‘Ok, I’m going to leave this money here and go do this.’”

Nearly 20 years removed from the most impactful decision of his life, one of the greatest athletes Colorado has ever produced can say it was indeed the right choice.

“I look at the path I took, I took it for a reason because obviously it prepared me for what I’m doing now,” he says.

What he does now – after a long, often confusing and frustrating playing career, which included zero championships and much less winning than he was accustomed to – is work for the Chicago Cubs. This spring, along with the rest of the organization, he’ll receive a World Series ring. Though he wasn’t a player, McDonald played a unique bit part in helping the team win what will surely be one of the most legendary championships in sports history.

***

Any discussion of Colorado’s best prep athletes has to include McDonald. He attended Cherry Creek when the school annually competed for championships in all major sports, and he was the star among stars. The Bruins were already a football powerhouse before he arrived, but with McDonald running roughshod out of the backfield, they captured three state titles in a row in ’94, ’95 and ’96.

Coaches didn’t allow freshmen to suit up on varsity back then, and he barely played at all in ’93 because he broke his collarbone. But McDonald amassed 6,121 yards over the following three years, a state record for 11-man football at the time. He also found the end zone 83 times (27.7 per season).

He was just as prolific on the diamond. McDonald did play four years of varsity baseball, becoming one of just five freshmen to start for Coach Marc Johnson during his 45 years (and counting) at Cherry Creek. McDonald hit .358 in ’94, validating his coach’s decision.

“I had a father that came to me and said, ‘How can this kid start? He’s a freshman.’ And I had to say to him, ‘Come and watch our practice for two weeks and you tell me how he doesn’t play.’ He just stood out,” Johnson says.

McDonald hit .581 with 15 home runs in 22 games as a junior, and .606 with 10 home runs in 22 games as a senior. Those numbers could’ve been better, Johnson says, if teams would have pitched to him more.

McDonald played little league ball with Johnson’s son, Tyler, but the coach’s first real indication of his talent came when an eighth-grade McDonald crushed a shot off the high school field’s scoreboard in left. He boasted an “Adonis type body” at that age and didn’t even start lifting weights until he started football at Creek, Johnson says. The coach knew by McDonald’s sophomore season that he’d be a draft choice; the only question was how high he’d go.

“This kid was a man among boys, even when he first came in,” Johnson says.

The ’95 state title stands as one of McDonald’s prep baseball highlights, as Creek defeated Arvada West, 6-3. The opposing pitcher was Roy Halladay, who’d go on to win two Cy Young Awards and make eight MLB All-Star appearances. And there was also the postseason game against Standley Lake in a late-spring snowstorm. Creek was “on the ropes,” according to Johnson, but got back to within a couple runs before McDonald won the game in the bottom of the seventh with a bomb in a snowstorm.

Yet, McDonald’s ultimate high school highlight came on the football field. Creek and its longtime rival Mullen met in the ’96 state semifinals, though Creek was just happy to be there considering the week it had leading up to the game. The father of one of the team’s starting defensive tackles was tragically killed, and real life dampened the magnitude of the game.

The Creek season appeared over when Mullen, playing at home, pulled out in front by 17 points with fewer than five minutes to go. “We looked to the sidelines and Mullen kids are shaking hands and congratulating each other and talking to people in the stands,” says Mike Woolford, the Creek head coach at the time.

But the Bruins soon scored to trim the lead, got the onside kick and quickly scored two more times to take the lead. Mullen still had time, though, and drove into field goal range. As they tried to kill the clock, the quarterback took two steps back, cocked his arm to fake a throw, then spiked the ball. Time expired during that fake, and Creek escaped with the win.

“It was probably as exciting a game as I’ve ever been involved in,” Woolford says.

McDonald remembers being afraid of a letdown the next week in the championship game. The Bruins would face Arvada West, quarterbacked by Steve Cutlip, who was getting nearly as many scholarship offers as McDonald. But the Bruins just rode their star. In his final high school football game, McDonald totaled 333 yards rushing and five touchdowns in a 48-33 shootout.

“He just had such God-given talent and was absolutely the best skilled [football player] that I’ve seen come through [Cherry Creek], and still to this day,” Woolford says.

“He’s definitely one of the finest athletes that’s ever come out of Colorado,” Johnson says. “No question about it, as a football player or baseball player. Either way.”

The athleticism was certainly aided by his family tree. His mother, Nina, ran for the famed Santa Monica Track Club. His father, Donzell, signed with the Pirates before getting hurt, going back to school and landing on the Colorado State football team as a defensive back. Nina also attended classes in Fort Collins, where Darnell was born in November 1978.

Then there were Donzell’s brothers. Ben McDonald spent four years in the NBA with Cleveland and Golden State (1985-89). Their other brother, James, spent four years in the NFL with the L.A. Rams and Detroit (1983-85, ’87).

The next generation of McDonald pro athletes began with Darnell’s older brother, Donzell Jr. He too played at Creek, but didn’t really develop in baseball until he arrived at Trinidad State Junior College. The Yankees took him in the 22nd round of the ’95 draft; he eventually appeared in 15 MLB games with New York and Kansas City and lasted 16 years professionally between the U.S. and Mexico. Donzell’s and Darnell’s younger half-brother, Darin, who also played at Creek, was drafted by the Phillies out of high school (12th round in 2006), lasted three years in the minors, then went to Wyoming for football before transferring to Northern Colorado. And their cousin, James Jr., who grew up in California, spent 10 seasons in pro ball, parts of six in the majors with the Dodgers and Pirates.

Darnell and Donzell occasionally saw their uncles play in person, sometimes meeting their teammates as well. One such summer trip took them to the house of a running back they often emulated, Eric Dickerson, who played with Uncle James. Darnell remembers an amazing house and the star’s two big German Rottweilers. With Uncle Ben, they mingled with Warriors standouts such as Chris Mullin and Manute Bol.

“Seeing this stuff at a young age was inspiring,” Darnell says. “We didn’t obviously know if we were going to play baseball or what, but my brother and I definitely grew up knowing that we wanted to be professional athletes.”

Yet, generous genes and familiarity with the professional level didn’t swallow McDonald and spit him out with a sense of entitlement.

“The thing that really is unique about Darnell is the fact that everybody thought, ‘Well, it was just his God-given talent that got him where he was,’” Woolford says. “But the kid worked really hard. He had a good work ethic. I mean he was a superstar; he could’ve let it go to his head and just kind of backed off. And you see a lot of those guys that do that and never reach the goals that they should reach.”

With all the hype and accolades McDonald toted around, the goals and expectations were lofty. To some, he fell short. To McDonald, it was all a journey to end up right where he was supposed to.

***

From Delmarva to Frederick to Bowie, McDonald spent his first three seasons in Class A and AA ball. He made it to the AAA Rochester (N.Y.) squad in 2001, when he could’ve been a part of the Texas football squad that finished No. 5 in the country at 11-2. He bounced between Rochester and Bowie in 2002, when he could’ve been a part of the Texas baseball team that won the College World Series.

McDonald didn’t crack a major league lineup until April 30, 2004, at 25 years old in his seventh season of pro baseball – not as quickly as the Orioles would have liked their first-rounder to make the big league squad, but at least he made it. The stint lasted 17 games and 34 plate appearances.

He didn’t see the majors again until four games with Minnesota in 2007. Two years later he managed 47 games with Cincinnati, including his first trip as a professional to Denver’s Coors Field. He went 0-for-4 with three strikeouts.

But the 2010 season, at 31 years old with Boston, saw McDonald finally stick in the majors. He played 117 games for the Red Sox, hitting .270 with nine home runs. His first appearance for the club was one for the storybook. Pinch hitting in the bottom of the eighth against the Rangers, McDonald became just the ninth Red Sox player to homer in his first at-bat for the team. His two-run shot over the Green Monster tied the game. Then he won the game with an RBI single off the wall in the bottom of the ninth, becoming the first Red Sox player with a walk-off RBI in his club debut.

“I couldn’t write a script any better than this,” he told reporters afterward. “A lot happened. A dream come true. That’s why I signed over here, to be able to play in this type of atmosphere.”

Centerfield was his to start the next day, and he homered again in the fourth, helping Boston to another one-run win. Prior to those two days, it took McDonald 147 major league at-bats to record two home runs.

The peak soon led to another valley, however. He made his first opening day roster in 2011, but played only 79 games for the Red Sox. The team released him in June 2012 and he was claimed days later by the Yankees. He saw action in only four games before falling back down to AAA.

McDonald joined the Cubs as a free agent in 2013, but stayed in AAA until August. He finished out the season in the majors, but saw game action only 25 times. With a single in one at-bat in a 4-0 loss to St. Louis on Sept. 29, his playing career effectively ended. When he didn’t make the big league squad out of spring training in 2014, he retired.

***

It wasn’t the career McDonald dreamed of, but 16 seasons in professional baseball isn’t an easy feat. Often, especially early on, he wondered if football would have been the better route. He could’ve matured in a college program. He would’ve loved the camaraderie of the ultimate team sport, instead of playing in a largely independent “business” as a teenager. He would have had a stronger support system when his 42-year-old mother suddenly died of a heart attack in 1999.

“I always think about that: What kind of player would I have been in college?” McDonald says. “How does that translate? But just the wear and tear on your body, and then now knowing what we know now about the head [concussions] stuff, I wouldn’t want my son to play football. Then it brings me back to reality and understanding why I went and played baseball – because I wouldn’t have played 16 years, probably, in football.”

McDonald’s son, Kingston, is the youngest of his four children and his only boy. At 9-months-old, he followed Jiana (11), Zuri (6) and Mila (4). McDonald was married, but went through a divorce toward the end of his playing career. “Probably the toughest time of my life,” he says. He turned to yoga and meditation to deal with the stress and read a lot of books, including a couple by Russell Simmons, the hip-hop mogul and renowned meditation advocate.

These “mindfulness” practices had evolved into his daily routine by the time he joined the Cubs, who, with Theo Epstein at the helm, were exploring the idea of a mental skills program. McDonald was hired as a baseball operations assistant within weeks of his retirement and initially tasked with helping the club’s player development and amateur scouting departments. But when Epstein officially announced the establishment of a mental skills program before the 2015 season, McDonald was named mental skills coordinator, reporting to director Josh Lifrak.

The Cubs then paid for McDonald to delve further into the mindfulness and meditation concepts he was already practicing and work on translating those to players at all levels of the Cubs organization.

“At the end of my career I was getting into yoga and meditation, and it was something that I was doing for me,” says McDonald, now a certified yoga teacher. “Now it’s a part of our mental skills program, giving our players an opportunity or the resources to understand it’s a skill, the skill of being present. So just like you develop all your other skills of swinging a bat, throwing a baseball, you can develop your mental side.”

The Cubs are among the first sports franchises to establish such a program, but McDonald believes nearly every club will have one in the next five years. Chicago winning the World Series this past season only helps validate its effectiveness.

“I wish I would’ve understood when I played is that this was also a skill, and that I could work on this also,” McDonald says. “I spent so much time working on all these other skills and now, looking back, if I could change anything about my career, it’d have been this, working more on the mental side.”

This new career involves passing his knowledge on to current players. Epstein and the Cubs thought him the perfect man for the job considering his journeyman background.

“If you look at my career, I was on every side there is. I was the prospect, I was the suspect (suspended for 15 games in ’05 for violating steroid policy), I was the guy fighting for the 25th job, I’d been released. So I [am] kind of able to relate to all our players,” he says.

He wouldn’t be able to relate if he became the superstar many predicted he’d be. He wouldn’t be able to relate if he quit baseball when it got tough and went back to football. He wouldn’t even have the job if he chose football on that fateful decision day after high school. And if he had chosen football, he wouldn’t be getting a World Series ring for his role in helping the Cubs quench the longest championship drought in North American sports history.

Twenty years after developing into one of Colorado’s greatest high school athletes, McDonald is not where he imagined he’d be. But he’s right where he’s supposed to be.

“You just look back and see how things happen,” he says. “All these things happen for a reason.”