This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Click here to read the full digital issue.

It took Willie Green a long time to understand it. He never asked his father, who didn’t seem to mind. Maybe his dad preferred playing on golf courses that looked more like off-road race tracks. Perhaps the other courses around Athens, Ga., the ones with the lush fairways and locker rooms and fresh seafood in the dining room, made him feel uncomfortable.

“Don’t know why,” Willie thought. “They look good to me.”

Too bad. He said his father, a janitor in a theater and post office, was a scratch golfer. That’s a mean trick when a good drive can disappear into a fairway full of dandelions. His clubs didn’t even match. It took Willie a few years of driving his dad’s golf cart during his rounds to finally figured it out.

His father, also Willie Green, couldn’t play in the country clubs and private courses because of the color of his skin. That’s why the Ku Klux Klan marched through their town. This isn’t the 1950s South. This is the 1970s.

“I took that personally,” Willie says.

So a young Willie Green set a goal. It wasn’t to become a star receiver at Mississippi or play eight years in the NFL. He wanted his father to play on a nice golf course. What did “Little” Willie Green do?

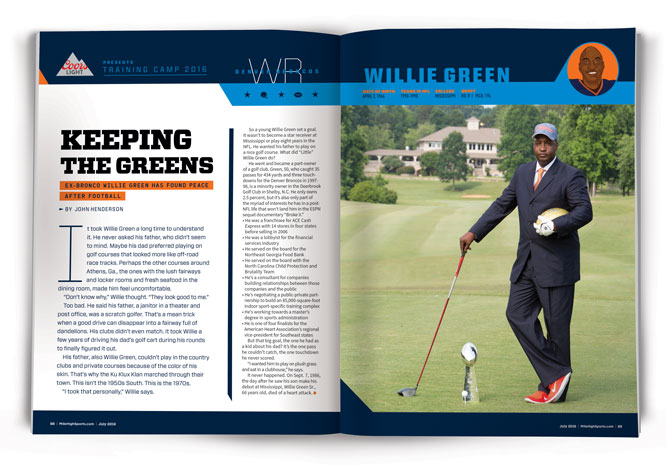

He went and became a part-owner of a golf club. Green, 50, who caught 35 passes for 434 yards and three touchdowns for the Denver Broncos in 1997-98, is a minority owner in the Deerbrook Golf Club in Shelby, N.C. He only owns 2.5 percent, but it’s also only part of the myriad of interests he has in a post-NFL life that won’t land him in the ESPN sequel documentary “Broke II.”

- He was a franchisee for ACE Cash Express with 14 stores in four states before selling in 2006

- He was a lobbyist for the financial services industry

- He served on the board for the Northeast Georgia Food Bank

- He served on the board with the North Carolina Child Protection and Brutality Team

- He’s a consultant for companies building relationships between those companies and the public

- He’s negotiating a public-private partnership to build an 85,000-square-foot indoor sport-specific training complex

- He’s working towards a master’s degree in sports administration.

- He is one of four finalists for the American Heart Association’s regional vice-president for Southeast states

But that big goal, the one he had as a kid about his dad? It’s the one pass he couldn’t catch, the one touchdown he never scored.

“I wanted him to play on plush grass and eat in a clubhouse,” he says.

It never happened. On Sept. 7, 1986, the day after he saw his son make his debut at Mississippi, Willie Green Sr., 66 years old, died of a heart attack.

***

“Little” Willie Green is talking on his cell while driving through rural South Carolina. He’s returning from a speech he gave to a graduation class at an elementary school in Athens. He talked about a popular theme of ex-pro athletes. Be smart, not cool. Don’t do drugs. Don’t do alcohol. The problem with those speeches is a few years later, the athlete who gave that speech is flat broke and no one will listen to him anymore.

But Green added an anecdote. It’s a story from when he was their age but strikes to the heart of why this “Where Are They Now?” story isn’t sprinkled with the words “bankruptcy,” “palimony” and “rehab.” When he was in fifth grade, with about 10 days before the school year ended, he was on a playground throwing rocks with friends at recess. One he threw hit a little girl. The principal, who had recently paddled him for another transgression, suspended him for the rest of the year.

“My mom whipped my butt,” he says. “My dad whipped my butt. My dad and I walked back to the school and he made me beg to get back in school. He said, ‘If you don’t get back in school, you’re not going to play sports.’ Sports were my life.”

Then his father said something that changed his life forever.

“Son,” he said, “you’ve got to start making better decisions. You’ve got to start making decisions based on the right thing, not the popular thing.”

His father raised nine kids in the Athens projects and was married for 30 years when he died. His father, not Jerry Rice, was who Willie Green followed. In the scrap heap of ex-pro athletes who face plant after retirement, Green says you can find a common theme in those players who don’t.

He had it.

“Look at guys who’ve been successful,” he says. “Most of the guys in the NFL and NBA, very seldom do you see an athlete get in trouble who has a strong father figure. Anybody can be a dad, get a woman pregnant and not do anything. But a father is there through thick and thin.

“Kobe Bryant. Shaquille O’Neal. Tiger Woods. Michael Jordan. John Elway. Look at those guys. I’m not saying you can’t be successful. But it makes a helluva difference to have a father. They keep you grounded. Fathers, they don’t care how much money you make. They care that you’re able to be a respectable young man and can take care of your family and responsibilities. I guarantee you, ask guys in the NFL, Major League Baseball, NBA, when they made it, did their dad ask for anything? Absolutely not.”

So in 1986 he went to Ole Miss, where the Rebel flag couldn’t possibly insult him any more than what he’d experienced in Georgia. He learned to live with it. He learned to stay away from it. But to his future NFL teammates, he always received the same question.

Ole Miss? Really? How bad was it?

“My only answer was, No. 1, racism is everywhere,” Green says. “No. 2, at least in the South you know here you stand with people. You know the racism. You see them with the Rebel flag. You see them with the sheets on. But you work with a guy in Oregon or New York or California who wears a suit and tie every day, you don’t know he’s the Grand Dragon.”

Undistracted, Green went on to catch 126 passes for 2,274 yards and 12 touchdowns. The only thing more popular in Southeastern Conference schools than a football player are the parties before and after fans watch him play. At Ole Miss, Sunday is not only a rest day for players but for partiers.

Green didn’t join the crowd.

“I was a designated driver before there was a designated driver,” he says.

He carried that into the NFL. A bonus baby he was not. Drafted by Detroit back when the NFL actually had an eighth round, he signed for a $15,000 bonus. His salary went from $65,000 his rookie year to $75,000 his second year. He was a serviceable receiver. He caught 39 passes for 592 yards and seven touchdowns as a rookie in 1991 (he was on the practice squad all of 1990) in helping the Lions reach the NFC Championship Game.

“When I was with Detroit,” he says, “auto workers and plant managers were making more money than I was.”

Detroit cut him after the ’93 season; he spent one year with Tampa Bay then became one of the first 10 players to join the 1995 expansion Carolina Panthers. Then came some decent money, from $250,000 to $400,000. Then he signed with Denver for a $900,000 bonus and a $650,000 salary followed by a salary of $900,000.

Sounds like enough to retire to a chateau in the Rockies, doesn’t it? According to the 2012 ESPN documentary, “Broke,” 78 percent of all NFL players declare bankruptcy or suffer financial stress within two years of retirement. Start with NFL’s constants of nearly 50 percent of the salary taken for taxes and agents getting 3-4 percent. That’s before you add the necessary house and car.

Then the financial nightmare really begins.

“These players work inside a bubble and inside that bubble you have your parents, you have your entourage and your home boy, other family members, your girlfriend or girlfriends,” he says. “There’s nobody in that bubble telling you no. It’s like having a strong father. That father is a counterbalance to all of those people.

“Then you’ve got your home boys who make you feel they helped you get there, that, ‘If it wasn’t for me, you wouldn’t be here.’ Now you’ve got to accommodate them for every game. They have no money. You take them out. You’re spending thousands of dollars a night trying to make them happy because they make you feel guilty.

“Then come the women. Now you’ve got a woman who ends up getting pregnant. Now you’re spending $5,000-$7,000 a month in child support. But before that’s final you’ve got to pay her lawyer and your lawyer $100,000-$200,000. Then you’ve got your mother and girlfriend competing. If you buy the momma a Mercedes you’ve got to buy the girlfriend a Mercedes.”

He remembers joining the Panthers with Lamar Lathon, the No. 15 overall pick out of Houston in 1990. He was an All-Pro in 1996. Every year he came to camp with a new car. One year it was a Ferrari, another a Lamborghini.

“Now he’s broke,” Green says. “I said, ‘What happened?’ He said, ‘I was trying to play God.’”

On the contrary, Green planned early. His mother, who ran a local recreation center, helped the cause. He tried to buy her a big house. She refused. He tried to buy her a Mercedes. She chose a Camry instead. “Mom said it would attract too much attention,” he says.

Green didn’t buy his first house until his fourth year, a $140,000 home in Stone Mountain, Ga. He and his wife and 18-year-old son, Willie II, still live in the same Shelby house he bought his last year in the league in 1998. While with the Broncos, they rented an apartment in Highlands Ranch. Like every other pro athlete, he was approached by investors as often as autograph hounds. But these guys wanted his signature for a different reason. Drugs and alcohol?

You can just say no to guys selling bar supplies, too.

“I never invested in restaurants,” he says. “I never invested in nightclubs because your employees will rob you blind. Most of these guys invest in these places then have a family member or friend running the place. That’s your biggest problem. They’re the ones ripping you off. The sad thing about it is they don’t even think they’re ripping you off. Their mindset is, ‘Ah, he got it. He won’t miss it.’”

With the Broncos, Green had a fellow grounded partner in receiver Rod Smith. The two would sit in the back of team planes and talk about their futures – the ones after their careers, not after their next game. Smith went undrafted out of Division II Missouri Southern but quickly became one of the top receivers in two Super Bowl runs.

The talks paid off. Smith, 46, is an independent representative of Organo Gold, a “healthy” coffee company that does business in 51 countries. Smith coaches and trains independent distributors, mostly in Colorado. He also does real estate and has a tech company worth about $230 million.

“We used to talk about it all the time,” said Smith on his way to Orlando for a coffee conference. “We’d see guys we played with and within a year or two when the game was over, they were done. They were done financially. It was really tough to sometimes watch. But at the same time, you can’t do anything about it.

“Willie’s first thing was his family. He was so intense. He was intense with his family. He loved his family, and everything he did was for them.”

As ex-teammates fell into financial ditches around him, Green made a plan. His wife, Dena, whom he met while with Carolina, had an accounting degree from Gardner-Webb. When they married in 1997 she returned to get her master’s degree. That November, they opened their first financial services company in Gastonia, N.C.

Green would buy underdeveloped stores from other small business owners. He’d run the day to day operations, build them up and sell them back to corporations. In 2006, he sold all 14 stores in North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida and Kentucky.

“I knew my (football) career was about to be over,” Green says. “I wanted to do something I enjoyed and do a smooth transition from the pros to the real world. When you retire, you’re 29, 30 years old. You have an entire life to live.”

After the sales, the trade association for financial services industry hired him as a consultant. He went to state capitals and Congress running go routes for his industry. He was a corporate development director of Outreach. However, one thing held him back from climbing that corporate ladder. After his senior season at Ole Miss, he quit school to concentrate on the draft. He had 100 of the 128 hours needed for a degree. In 2009, he was up for an evaluation and raise. Sorry, Willie, his boss at Outreach told him.

No degree, no raise.

“It’s one of the biggest mistakes I ever made,” Green says. “I don’t regret making mistakes, but I think I could’ve done both at the same time. I decided not to go to school. If I make it in the NFL, I don’t need college.”

Turns out he did. The boss, however, gave him time off to get his degree and he graduated in human services from Gardner-Webb in 2012. He’s now working on a master’s degree in sports administration at Ohio University. His thesis?

The transition college and pro athletes make to the real world.

“A college degree does make a difference,” he says. “With a degree I got stock options, a company car. I share this with college and pro players. Just because you’re an NFL player, you’re not going to get a job with that kind of money. Don’t give them a reason to not promote you because you don’t have a college degree.”

Then his climb up the ladder hit another broken step.

Cancer.

***

In April 2015, Dena was diagnosed with breast cancer. For Green, the C word hits him harder than a free safety ever did. His mother died of ovarian cancer 10 years ago. His two sisters, both heavy smokers, died of lung cancer within the last four years. (His 52-year-old brother died falling off a train trestle in 2003.)

“When my wife was diagnosed, it really put me in a panic mode,” Green says. “It just really scared me that I could lose her like I lost my mother and my sisters. I’ve always been a family person anyway. It made my wife and I a lot closer.”

The panic wasn’t necessary. Doctors caught it early and she’s recovered. Now he has the time and peace of mind to pursue his two latest interests: His son’s football career and golf. Willie Green II led Shelby’s Crest High School to a 32-0 record and two state titles his last two years. Last season, he threw for 3,600 yards with 35 touchdowns and eight interceptions while completing 70 percent of his passes for a rating of 143.6.

He has a 3.8 GPA and scored a 23 on his ACT. He’ll graduate with 24 hours of college credit. Unfortunately, he is only 6-foot-1. The biggest scholarship offer he received came from the East Tennessee State, an FCS school. Brown is interested but wants him to score a 24 on his ACT. Instead, he’s going to Palmetto Prep Academy in Columbia, S.C., then he’ll enroll somewhere in January.

“Nine out of 10 quarterbacks are going to redshirt anyway,” Willie I says. “I’m a product of a prep school. He’ll get another year of playing and get an opportunity to compete against JC and college-bound guys.”

Soon to be an empty nester, Green might work on his short game a little more. What’s the best part about being part owner of a golf club?

“I can play anytime I want,” he says. Although Smith says, “He has the ugliest compact swing. It looks like Charles Barkley’s but it goes straight.”

The venture began in 1997 when he joined about 10 other investors to build only the fifth public golf course in Cleveland County. It has just one private course. Since Deerbrook opened in 1999, two of the courses have closed, leaving Deerbrook to shine in a golf-crazed region. Greens fees for the private-public course are only $32, putting it No. 15 on GolfAdvisor.com’s top 20 best value courses in the country and No. 11 overall in North Carolina.

Since then, the number of investors has dropped to five. Although he only owns 2.5 percent, the lowest of the group, Green still goes to meetings and offers ideas.

“We’ve done real well,” he says. “There’s no loan on the property. We’re operating in the black. A lot of golf courses are struggling.”

He still wears his Super Bowl rings from ’97 and ’98 and tells the story about catching the pass that put John Elway over 50,000 yards. And the time he scored two touchdowns for the Lions in beating Dallas in the ’91 playoffs. And while with Carolina how he scored on an 89-yard reception on against Atlanta and handed the ball to one of the 40-50 kids he invited from Athens.

“My mom was in the stands,” he says. “It was the first game she ever came to. Mom didn’t hate football games. She hated to see me play football.”

She would love to see him sit in board rooms in a suit and tie and watch his son win state championships. So would his dad, who would’ve settled for a nice round of golf where the flag sticks weren’t made of wood.

Teammates and foes alike are looking around asking themselves where it all went. Nearly two decades after retiring, Willie Green is asking himself what can he do next.

John Henderson is a freelance writer based in Rome. Follow his travel blog at Johnhendersontravel.com.