This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition.

Frankfurt’s skyline doesn’t look quite right in the middle of Europe. Skyscrapers never do. On a continent of artsy churches, historic monuments and graceful architecture, Frankfurt’s steel landscape looks from a different world, like an MMA fighter on a ballet stage.

Viewing it from a sports perspective, however, there is no more suitable city for Germany’s only skyline. Frankfurt am Main, aptly known as Mainhattan, is not only the financial center of Germany; it towers over the country as its soccer center. As Germany is defending World Cup champion, feel free to label Frankfurt as the soccer center of the world.

Inside this steel jungle, on a cold, drizzly January day, drives a man dwarfed by his environment, not to mention his task at hand. Justin Rose maneuvers his Hyundai through the spotless streets of Westend, a quiet — no, dull — neighborhood occupied by serious German businessmen.

Rose, 42, is a serious American soccer hand, as ambitious as any of the Germans who built the buildings towering above him. He has gone from the 1993 Colorado High School Player of the Year at Arapahoe to a full ride at Clemson, to the Under-20 national team to these streets of Frankfurt 13 years ago with a coaching and consulting business, JRR Consulting.

As his neighbors begin buzzing over Germany defending its title in Russia this summer, Rose chews on his own nation choking like a band of rabid, gagging dogs and not even qualifying. Yet, swallowing the olive at Trinidad and Tobago, a country the size of San Diego, in that 2-1 loss Oct. 10 gave Rose all the more reason to dig his heels into the German concrete.

“My goal,” he says, “is to get Americans to win a World Cup.”

If that sounds like a mouse taking on a savannah full of lions, well, you’re right. But at least Rose is in the right place. Frankfurt is not only headquarters of the Bundesliga, the best-attended soccer league in the world, but also the Deutscher Fussball-Bund (DFB), the German soccer federation. Its office is located a long corner kick from 51,000-seat Commerzbank-Arena, home of Eintracht Frankfurt, one of 10 Bundesliga teams within 200 miles of each other.

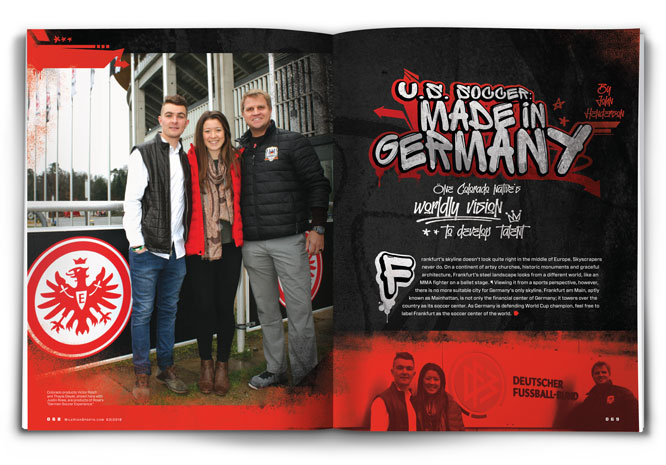

This is where Rose has launched his assault on U.S. Soccer’s future. He has been splitting his time between Colorado and Frankfurt with this idea: Using promising prospects, mostly from Colorado, Rose takes about three or four at a time to the bevy of soccer clubs and academies in the Frankfurt area. For at least eight days, at various costs, they train with them, go to games, study German and tackle life in a country where soccer is life.

It’s called the German Soccer Experience and in five years, Rose has taken more than 50 Colorado kids to Germany. Two even signed contracts and are playing here professionally. Victor Rolph, 21, played the first half of the season with fifth-division RW Frankfurt. Thalya Dwyer, 22, is playing for Eintracht Frankfurt’s third division women’s team. It stood in first place after the first half and could move to the second division at season’s end.

“The main thing is to get them over here and have that experience,” says Rose, who also brought over three Israelis who signed. “So when they go back home, they see what they want and what they want in life. It might be, ‘Man, that changed my life and it changed my path.’”

Rose parks near a dull, gray, three-story building. It’s the home of Lokalbahnhof, one of the best German coffee shops in the area. Good, creamy German coffee. Soft, dark, German bread. Yummy omelets and burgers in the day; big beers and house wine at night.

Above the cozy, wood-paneled restaurant is conveniently located the apartment of Dwyer and Rolph, who met during one season at La Junta’s Otero Junior College and have been together ever since. In good German, Rose orders a schorle, a popular German drink combining fruit juice with carbonated water, and talks about the gulf between German and American soccer.

Keep in mind that not too long ago Germany was down and nearly as out as the U.S. In the 2000 and ’04 European Championships, Germany never got out of the group stages, collecting zero wins, three draws and three defeats (0-3-3). What did the German federation do?

It forced every Bundesliga team to start a youth academy. Ten years later, it stood atop the world. It won the 2014 World Cup, won last summer’s Confederations Cup with essentially its B team and is a 9-2 favorite to win the World Cup again.

Every youth academy has a system that’s a mirror image of the Bundesliga club it represents. By the time players reach the Bundesliga or Bundesliga 2 second division, it’s a seamless transition. And the number of teams the DFB runs in divisions below Bundesliga 2 totals in the hundreds.

“Yeah, it’s easier to find the best players in Germany because of their system,” Rose says. “You can say the day-to-day competition. I’m a big fan of college education, but if you’re a great young talent and if your goal is to play professional soccer, especially in Europe, you have to come here when you’re 16, 17, 18 years old.”

The German federation has scouts all over the country. They place prospects in academies where they go to school and play soccer. The clubs tend to their every need.

The U.S. has developed soccer academies – including the Colorado Rapids Academy, which has produced a multitude of college and professional players, including current Rapids Kortne Ford and Dillon Serna, as well as Shane O’Neill. Both Serna and O’Neill spent time with the USMNT – but soccer remains primarily a bastion of the suburban class rather than the urban class. Unless you’re good enough to get invited to a youth academy, you’re looking at spending $5,000-$7,000 a year for soccer on an elite year-round team that likely prohibits you from playing for your high school.

“It’s still that way in America. The better you are the more you pay,” Rose says. “In Europe it’s completely different. The better you are, the less you pay.”

While the Bundesliga works together with the DFB, U.S. Soccer remains rudderless. The World Cup qualifying collapse resulted in the firing of coach Bruce Arena and the resignation of president Sunil Gulati. U.S. Soccer membership in February elected Carlos Cordeiro to replace Gulati. Now a coach must be found. Infighting remains between MLS and the two lower divisions: USL, which has 30 teams, and NASL, which has only eight. In September, the NASL sued U.S. Soccer for swapping its second-division status with the USL. It’s a mess worthy of reality TV.

Nearly 40 years after youth soccer participation started its steady rise, U.S. soccer remains in the world’s backwaters. It’s obvious the U.S. needs a new system.

“That’s where I come in,” Rose says with a smile.

***

The bell cow for Rose’s German Soccer Experience is Christian Pulisic. Borussia Dortmund, 130 miles north of Frankfurt, signed him out of Hershey, Pa., in February 2015 at the age of 16 and put him in their youth academy. By April 2016 Pulisic became the youngest foreigner to score in the Bundesliga. Today, at 19, he may be the best player on the U.S. squad and is one of the top, most sought-after players in the Bundesliga.

“He has become that player who has come over, learned the system, learned the language, learned the culture, learned to adapt,” Rose says. “Now guess what? He’s now one of the most highly rated players in Germany. He’s wanted by… you name it.

“And he’s an American.”

The example Pulisic provides is what Rose sells his players. The path to soccer greatness is much clearer in Germany where they’ve streamlined it into a well-oiled machine. In the U.S. the path looks like the L.A. freeway system — clogged, confusing and, sometimes, a complete waste of time.

German soccer is much like American football. Kids in the U.S. play youth football, then high school, then college. The very best get pro contracts. It’s a clear pyramid.

“In German soccer it’s the same way,” Rose says. “Here school and sports are separate, but here the kids are found and the best kids go up the triangle.”

To find players, he has parents fill out forms and send him videos as well as using his own network of contacts. Based on the league and film, Rose knows if a player is good enough to earn a trip to Germany. Surprisingly, he does not get inundated with desperate soccer moms saying they have the next Lionel Messi up the road in Thornton. Admittedly his email box did get busy after the U.S. bombed out of the World Cup, but he does not advertise.

“My way is to help out in a small way to find those players that have what it takes to play at the next level in Europe and to give them the chance to come here, test themselves, be seen and open up doors,” Rose says. “Because it’s their play that will ultimately open up doors, and I have the network here to do that.”

Rose just wishes someone was here for him when he was that age. No one in Colorado was more suited for a German Soccer Experience than Rose. Proud of his German heritage, by the time he was 8 he had a German flag on his bedroom wall. Bundesliga team photos filled his room. Every Wednesday and Saturday he sat glued to “Soccer Made in Germany” on TV. He was a regular at Dave Clements, which sold jerseys of German clubs most of his classmates couldn’t pronounce.

As much as interest hit him early, so did injuries. He had his first major surgery when he was 13. They didn’t discover he was born with an extra bone in his ankle until he broke it. He had sinus surgeries at Arapahoe and suffered a knee injury before his senior year. Still, he managed to lead the Warriors to the state title and earn the Player of the Year award.

Clemson coaches discovered him during a tournament in Florida and gave him a scholarship, but he broke his nose in his first league game. Then he injured his knee in training with the national team. By the time he was 20, he already had five surgeries and no more patience.

Tired, both mentally and physically, he quit soccer and transferred to Arizona State where he studied international business and how the mind, body and fitness all work hand in hand. That led to a consulting career that took him to Amazon in Seattle and to form his own company, which led to JJR Consulting today. He coached the Mullen High School girls team and assisted the Arapahoe boys team. Rose even attempted to resuscitate his soccer career through a tryout with the Rapids; his preparation was chronicled in the October 2003 edition of Mile High Sports Magazine.

He went to California to work with businesses and B-level actors, then to South Korea and Japan and to Germany where he continued his dream of soccer. All along the way, he put his consulting tools to good use. He has one message he gives all his prospects.

“Perception is reality,” he says. “What you perceive is what your reality is. Change your perception, change your reality. Every day is a new day. I don’t believe in bad days. I believe in bad moments.”

***

It’s nearing lunchtime and Dwyer and Rolph bound down the stairs into the restaurant. With long brown hair and a bright smile, Dwyer could pass for a college exchange student in Germany rather than a pro soccer player. Short and wiry with a buzz side cut and two earrings, Rolph has the hip appearance of world-weary backpacker

He arrived in Frankfurt a year ago. His German has reached the level where he can communicate with those teammates who don’t speak English. While they may miss out on college parties and their friends in the stands, the couple is living the dream of soccer players with views beyond American borders.

They like how most places are closed on Sunday, how people sit down for a meal and stay all evening. They like how breaking through the tough veneer of the Frankfurters you get a friend for life. “Like you become part of their family,” Dwyer says.

Up the road they can attend a pro soccer match in a packed stadium where 50,000 fans watch an Eintracht Frankfurt team that has never won the Bundesliga. The road from the train stop to the stadium is lined with beer and sausage shops and the breadth of Frankfurt society. It’s a Broncos tailgate party twice as many times a year. It’s soccer heaven.

Language wasn’t the only culture shock. They suffered it on the field, too. The American and German playing styles are as different as the words used to describe them.

“Something I noticed right away was the discipline of all the players,” Rolph says. “They play a more disciplined-style game. That’s something I’ve adapted to and is a great tool I have in my game now that I took from Germany.

“I wouldn’t say they’re not disciplined in America, but there’s more attention to detail here. Every little touch. The passes that should be completed are completed.”

For the women, Germany has shot up to No. 2 in the world ranking behind the U.S. and its Bundesliga is receiving respect around Europe. Dwyer may have had street cred coming from the global women’s soccer power, but it’s a different game here.

“In the U.S., playing college [soccer] there, you have to be fit,” she says. “You have to have really good endurance. Here there’s a lot more focus on the tactical side. It’s a good level I’m playing at. They’re good at knocking it around, connecting passes and going forward with it.”

They don’t make enough money to make ends meet. That’s okay. Their side gigs alone have made it worth moving to Germany. Dwyer is studying to be a veterinarian and her club set her up with an internship. Rose has some Colorado-based sponsors and they both work camps, including one with a handicapped adult team that has them both talking about continuing when their careers end.

“We showed up every day with the biggest smiles,” Dwyer says. “We left with the biggest smiles.”

How far they’ll go is up to them. Dwyer is only two good seasons from the first division through promotion. Rose says, “Oh, when she does stuff with the ball, everyone turns and watches. It’s fantastic. When she learns the system, she’ll be a Bundesliga player, without a doubt.”

Rolph just signed with Oberrad 05, a sixth-division team but of higher quality than RW Frankfurt. He says the difference between third and sixth division players is minute and the promotion of your coach could mean your promotion, too. He has the talent. A product of the Rapids Academy, he played with the likes of O’Neill and Serna.

“He reminds me of a Christian Pulisic,” Rose says. “The way he moves, the way he runs. The difference is that experience, the games, the confidence as he talked about. Christian Pulisic has that confidence.”

But unlike Dwyer, Rolph has a larger pile of bodies to climb over to reach his nirvana. Ralf Weitbrecht, a soccer writer for the Frankfurter Allgemeine newspaper for 29 years, said, “It’s possible. You have to be very lucky. You have to be very good. But to be honest, it’s almost impossible to go from fifth division to the Bundesliga. The players in the Bundesliga are in front. They are faster, more athletic. Because of the education they earned, the system in the second division is much better than the third or fourth division.”

But if you shoot for the stars and land on the moon, you can shoot for the Bundesliga and land somewhere else in the world. They’d both like to play in the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo. Dwyer’s parents are Australian, who split time between Colorado and Brisbane, and she has dual citizenship. They talk about playing for the national Under-23 teams.

Maybe some day, Rolph will be part of the American uprise that can challenge Germany. It’s a long wait, one the U.S. has waited for long enough. But underneath a different set of skyscrapers, Mainhattan represents that Big Apple in the German sky.

John Henderson is a freelancer in Rome. Follow his travel blog, Dog-Eared Passport, at www.johnhendersontravel.com.