This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition.

It was late August in Denver’s Five Points neighborhood, and nine-year-old Elvin Cousins couldn’t believe his good fortune. His father Norman, a Pullman porter for the Union Pacific railroad who also blew a cool sax some evenings at the Rossonian Hotel and Lounge on 27th and Welton, had just that morning at breakfast handed him a ticket to the 1936 Denver Post Base Ball (period spelling) Tournament.

Norman had been filling in for a sick member of Duke Ellington’s band the night before and some members of a Negro League all-star team were among the crowd packed into the Rossonian’s tiny triangular ballroom.

In reverent tones, Norman Cousins would tell his son about musicians like Ellington, Billie Holiday, Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald, all who came to Denver to play the Rossonian but, like the black baseball team, weren’t permitted to stay at downtown hotels like the Brown Palace. They’d play a set at a “white” hotel then play a later set at the Rossonian where they’d spend the night.

Elvin’s dad had told him all about the jazz greats, but his father didn’t know or care a lick about baseball. He said a Mister Bell had given him the ticket.

Elvin knew all about Mister Bell, but he knew him as “Cool Papa” Bell who played centerfield for the Pittsburgh Crawfords. People said that “Cool Papa” was faster than Jesse Owens, a Negro American who had just won four gold medals a couple of weeks prior at the Olympics in Berlin. “Mister Bell,” Elvin laughed to himself. He loved his dad but couldn’t believe how little he knew about baseball.

From reading the Denver Post, Elvin knew that “Cool Papa” was a part of the Negro League all-star team that was entered in the tournament. It seemed strange to Elvin that black and white players would play on the same field, but he’d heard that two black players – Oliver Hazzard “The Ghost” Marcelle and Poss Parsons had played in the Denver Post Tournament in 1934.

He also knew that “Cool Papa” was just one of a bunch of great Negro League players on the team. The greatest pitcher of all-time, Satchel Paige, would probably start the game today against the Bay Refiners which featured one of the greatest white players, Rogers Hornsby, who was finishing out his Hall of Fame career with the St. Louis Browns. And none other than Josh Gibson, another Crawford and the greatest home run hitter of all-time (including Babe Ruth) would be catching Satch. If that wasn’t enough, Buck Leonard of the Homestead Grays would be playing first base.

Even the prospect of an hour-and-a-half walk from Welton on Five Points down Broadway to Merchants Park couldn’t dampen Elvin’s enthusiasm. He could have taken the Denver Tramway trolley, but he wanted to save his money for a hot dog and a box of Cracker Jack at the ballpark.

It took him a while to get going from Five Points because everyone stopped him to say hello and pass on greetings to his dad and his mom who sang in the choir at the Shorter AME Church. He loved the way the neighborhood felt like a big family. He was nervous about venturing outside of it today, but to see his baseball heroes would be worth it. He went by the Ex-Servicemen’s Club, owned by Bennie Hooper, whom a lot of people called “The Mayor of Five Points,” and past restaurants where he ate with his parents on special occasions – Ethel’s House of Soul, Zona’s Cafeteria and the Ritz Café, where on Sundays after church they had “Grits at the Ritz.”

His mind on baseball, he hustled past the Da-Nite Service Station, Busy Bee Cleaners, and DeWitt’s Barber Shop where he often stopped to talk. But not today. He did slow down, out of respect, as he went by the house where he was born. It belonged to Justina Ford, the doctor who delivered him and almost every other baby born in Five Points since 1902. He didn’t even stop when Mr. Samuel Eddy Curry waved to him from his porch. Mr. Curry was the first black man to practice law in Denver, and he had gotten his dad out of a scrape when a man falsely accused him of stealing his watch at Union Station.

Hitting Broadway, he picked up his pace. He knew no one would be greeting him. He walked in the shadows of the buildings, kept his eyes down and tried to remain inconspicuous. Past Sears, Roebuck & Co., past the Brown Palace and Hotel Shirley Savoy – where he knew his dad’s music friends played. Then past the Western Union office, Foster Auto Supply and the intimidating State Capitol at Colfax and Broadway. He’d heard there was once a ballpark called Broadway Grounds, right across Broadway from the Capitol, in front of the Daniels & Fisher Tower. He wished it were there now.

Only 20 blocks to go as he passed Western Auto Supply, the B.K. Sweeney Electrical Company and Franklin Studebaker. His family had no car and he knew nothing about them. But he couldn’t stop staring at two shiny new models, a pale green Dictator and a bright yellow President. Wishing for a new ball glove was more realistic.

He crossed over to the east side of Broadway when he saw the Jonas Furs sign. He’d heard his mom joke with his dad that she wanted a fur coat for Christmas. Two elegant, pale mannequins were in the Jonas window, one wearing a squirrel coat, the other an Alaskan seal stole. When he saw the prices he knew why his mom was joking about owning one.

A couple of blocks later he sprinted past Willy-Overland Fine Motor Cars. He was more of a Studebaker man. Then, as he neared Cherry Creek, he looked for the ballpark where the Denver Post Tournament had begun in 1915 and where the Denver Bears and the Denver White Elephants had played. The White Elephants were the only baseball team his dad had ever mentioned (and that was because they were an independent Negro team organized by Mr. Ross, who owned the Rossonian). But Broadway Park II (the first had burned down) was nowhere to be seen.

In five more blocks he stood before the Mayan Theatre at First and Broadway. He stared up at the exotic chieftain peering down at him from above the Mayan’s sign. He saw that there was a double feature – “Charlie Chan at the Circus” and “Mutiny on the Bounty” with Clark Gable. He thought, briefly, that if he had a ticket he might rather see Charlie Chan than Satchel Paige. No, he’d rather see the Negro League all-stars than meet Charlie Chan in person.

Another block and he was at Desserich’s window, which was displaying the 1937 Philco Radio, yours for a dollar down and a dollar week. Elvin heard a ballgame once on the radio at DeWitt’s Barber Shop, but he knew his dad would buy something only if he had the cash.

After Murphy’s Fine Foods, he was finally on South Broadway where he passed the Goodrich Silverton Store. Up ahead on the west side of the street, at 555 S. Broadway, he saw Montgomery Ward (three shirts for $2.75). He knew just past that was Merchants Park.

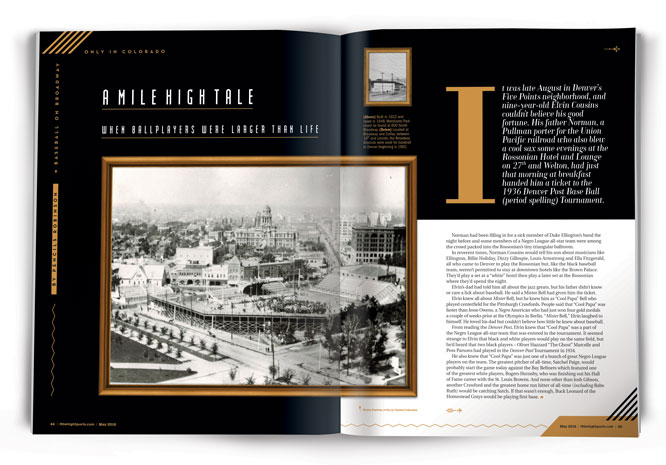

Walking through the turnstile, ticket in sweating hand, was the greatest feeling Elvin had ever had. But it was nothing compared to what he felt when he emerged from under the huge wooden grandstand and beheld the chalked diamond, the brilliantly white bases and the perfectly graded brown dirt. He’d read that the centerfield fence was over 450 feet from home plate and that Judy Cline (1932) and Babe Ruth (1927) were the only two men have ever hit a home run over the centerfield fence, each in the Denver Post Tournament.

Elvin saw that despite all his stops along the way, it was only 3:30 and the game wasn’t scheduled to start until 5 o’clock. The scoreboard showed that the second game of the day had ended with Clear Vision Pump of Kansas defeating the Denver Elitchs, 4-2. As those players were leaving the field, the Negro League all-stars bounded on, laughing, insulting each other, tossing balls so high in the air Elvin thought they’d never come down. If his dad’s jazz musicians were great men and women, these ballplayers were gods. And the gods were going to play baseball right on Broadway, less than four miles from his house.

He was transfixed. Batting practice – with Gibson and Leonard ricocheting shot after shot off the fences and “Cool Papa” chasing down every ball that didn‘t hit the fence – was over in an instant and before he knew it somebody was shouting, “Grab a seat, kid. The game’s gonna start.” He took a quick look around and realized that the only other black faces to be seen were on the field. He scurried to a seat in the far corner of the bleachers that extended halfway to right field.

The game was over too soon. Paige, who had just turned 30 and at 6-foot-3 looked like a willow tree to Elvin, pitched like a man who couldn’t wait to have a cool drink and listen to Duke Ellington back at the Rossonian.

He struck out 15 Bay Refiners on fastballs that sounded like lightning cracking into Gibson’s mitt and an occasional curve ball that had the batter lunging at a pitch that bounced two feet in front of home plate. In the top of the seventh, with the score tied 0-0, Paige told his fielders to sit down and then proceeded to strike out the side. Through nine innings, he gave up only one hit, an opposite field double off the right field fence by Hornsby, who on his last at-bat in the top of the ninth was robbed of a home run when Bell raced behind his left fielder and grabbed a blast that was headed out of the park.

It was still light out when the Negro League all-stars came to the plate with the game tied zip-zip. Although they were always proud to turn on the lights at Merchant Park (which had been installed in 1930, five years before Cincinnati’s Crosley Field became the first major league park to have lights), there was no need to do so as the sun was still peeking out from behind the Rockies. And the Post didn’t want to spend money it didn’t have to. Those bulbs burnt out all the time and were hard to replace.

To Elvin’s – and everyone else’s – amazement, the Bay Refiners’ pitcher, number 21, a 6-foot-4 left-handed orphan named Kid Finch, who had been adopted by a couple in Limon and grew up tossing hay bales on their cattle ranch, had shut down the Negro Leaguers as effectively as Paige had frustrated the Refiners. Finch, who had just turned 16 on April 1, had shut down possibly the greatest group of hitters ever assembled at one time in Denver. No one – not Gibson, not Leonard – had gotten a ball out of the infield against the Kid. The all-stars had only two hits, both by “Cool Papa,” both comebackers to Finch that only “Cool Papa” Bell could have beaten out.

Now, with two outs and Elvin still entranced but starting to think about dinner (he had totally forgotten to buy a hot dog or Cracker Jack), Josh Gibson stepped to the plate and glowered at the pimply-faced, knuckle-dragging galoot who had no business being on the same field as the all-stars, much less holding them scoreless.

Gibson smoldered, too, with the knowledge that he should have been playing in Yankee Stadium with Ruth and Gehrig instead of in this bush league ballpark in a second-rate town where he couldn’t sleep in a first-rate bed. The irony of playing simultaneously on- and off-Broadway was not lost on Josh Gibson.

Finch did not flinch.

He threw the only pitch he knew how to throw. The one he called the Barn Buster. The one some old-timers who were there that evening at Merchants Park still swear that if they’d had a radar gun in 1936 it would have maxed it out.

But Gibson, only 24 and a bullish 6-foot-1, 210-pounder, didn’t flinch either. Some say no one in the stands ever saw the pitch. Some say Gibson had better ears than eyes. Some say the workers reporting for the night shift at Montgomery Ward hit the deck as if they’d just heard a machine gun blast from the Red Baron’s Fokker.

But everyone agreed that the ball was still rising when it cleared that oh-so-distant centerfield fence at Merchants Park. Gibson didn’t stand at the plate and watch the ball. The greatest home run hitter of all-time didn’t flip his bat. He immediately began the world-weary trot that he had used on every home run he had ever hit.

Some say he looked up only once, just before rounding first, when he saw the only black face in the crowd. Some say he winked at the kid sitting alone in the corner of the bleachers, which were halfway to right field.

Some say it was too dark to tell.