This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition.

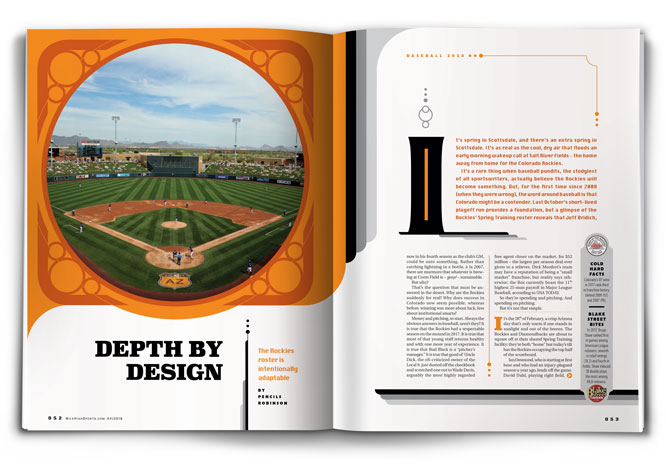

It’s spring in Scottsdale, and there’s an extra spring in Scottsdale. It’s as real as the cool, dry air that floods an early morning wakeup call at Salt River Fields – the home away from home for the Colorado Rockies.

It’s a rare thing when baseball pundits, the stodgiest of all sportswriters, actually believe the Rockies will become something. But, for the first time since 2008 (when they were wrong), the word around baseball is that Colorado might be a contender. Last October’s short-lived playoff run provides a foundation, but a glimpse of the Rockies’ Spring Training roster reveals that Jeff Bridich, now in his fourth season as the club’s GM, could be onto something. Rather than catching lightning in a bottle, à la 2007, there are murmurs that whatever is brewing at Coors Field is – gasp! – sustainable.

But why?

That’s the question that must be answered in the desert. Why are the Rockies suddenly for real? Why does success in Colorado now seem possible, whereas before, winning was more about luck, less about institutional smarts?

Money and pitching, to start. Always the obvious answers in baseball, aren’t they? It is true that the Rockies had a respectable season on the mound in 2017. It is true that most of that young staff returns healthy and with one more year of experience. It is true that Bud Black is a “pitcher’s manager.” It is true that good ol’ Uncle Dick, the oft-criticized owner of the Local 9, just dusted off the checkbook and scratched one out to Wade Davis, arguably the most highly regarded free agent closer on the market, for $52 million – the largest per-season deal ever given to a reliever. Dick Monfort’s team may have a reputation of being a “small market” franchise, but reality says otherwise; the Rox as of mid-Spring Training boasted the 11th highest 25-man payroll in Major League Baseball, according to USA TODAY. (Editor’s note: They ranked 14th on Opening Day.)

So they’re spending and pitching. And spending on pitching.

But it’s not that simple.

Apr 4, 2018; San Diego, CA, USA; Colorado Rockies relief pitcher Wade Davis (71) pitches during the ninth inning for the save against the San Diego Padres at Petco Park. Mandatory Credit: Jake Roth-USA TODAY Sports

It’s the 28th of February, a crisp Arizona day that’s only warm if one stands in sunlight and out of the breeze. The Rockies and Diamondbacks are about to square off at their shared Spring Training facility; they’re both “home” but today’s tilt has the Rockies occupying the top half of the scoreboard.

Ian Desmond, who is starting at first base and who had an injury-plagued season a year ago, leads off the game. David Dahl, playing right field, hits second. Dahl is one of those players, when seen at Spring Training, who jogs the memory.

Remember that guy? That’s the player who had a 17-game hitting streak, tying a major league record, to begin his career two seasons ago. That’s the player who couldn’t find the field at all last season because of injury. If he’s healthy, he should be a valuable asset in the Rockies outfield, which is exactly the hope of everyone within the organization.

Seeing Desmond and Dahl go 0-for-2 to begin the game doesn’t feel unusual until Charlie Blackmon steps into the batters box hitting third. Blackmon? Wasn’t he MLB’s best leadoff man a season ago? It’s a question that’s been batted around all spring already – why Blackmon is hitting third – and one that will continue to be posed well into March. The logic is that Blackmon’s 2017 RBI total was somewhat of a fluke. Not because Blackmon got lucky – his bat was red-hot all summer long – but because his manager believes the traffic on base when his leadoff man was hitting last season was unusually high. Putting Blackmon in the three-hole ensures that traffic will be there, leaving nothing to chance for one of the team’s best hitters.

Four through nine: Chris Iannetta, who the Rockies believe will be a major league version of Crash Davis for the team’s young pitching staff; Tom Murphy, who today has DH duties, but will presumably provide depth at catcher; Ryan McMahon, probably the most buzz-worthy Rockie at Spring Training, who’s playing third on this particular day but most believe will be the team’s answer at first base in the very near future; Raimel Tapia, who went from prospect to regular contributor last season; Shawn O’Malley, a highly thought-of journeyman but because of injury may not crack the Opening Day roster; and Daniel Castro, a shortstop who would have to clear plenty of hurdles to see time at Coors Field this summer.

It’s the interesting thing about Spring Training; barring injury or contract situations, the story is never about the team’s stars. The only scuttlebutt on that front is Nolan Arenado’s open endorsement to re-sign (then) free agent Carlos Gonzalez. Otherwise, the talk is about the youngsters, players like McMahon, Tapia, Mike Tauchman (who, on this day, would replace Blackmon in center and proceed to double; against the Cubs the next day, Tauchman would go 1-for-2), shortstop Brendan Rodgers and outfielder Noel Cuevas.

Not exactly household names back in Denver, but down in the desert that’s all anyone wants to discuss.

Mar 6, 2018; Peoria, AZ, USA; Colorado Rockies third baseman Ryan McMahon (24) throws to first base against the Seattle Mariners during the third inning at Peoria Sports Complex. Mandatory Credit: Joe Camporeale-USA TODAY Sports

To point, the very next morning, Bud Black is asked about McMahon. After all, through five games and 11 at bats, McMahon is hitting .500, a mark that doesn’t go unnoticed. (Note: McMahon still managed a .319 average by the conclusion of Spring Training.)

A reporter suggests that McMahon is having an excellent spring. Black is careful not to laud his young first/third baseman with too much praise. He agrees, but points out that statistically McMahon is enjoying the spring. It’s a subtle distinction, but one that hints there’s still ground to be covered.

McMahon is one of several young players that is not only playing well, but can play more than one position. In two days’ time, McMahon gets starts at both third and first. As the spring unfolds, multiple players – veterans and rookies alike – play multiple fielding positions and hit in various slots.

This is not by accident. This is the new way of doing business for the Colorado Rockies – depth and flexibility.

“The versatility that these guys bring is advantageous,” Black tells the gathered media.

He’ll offer that answer in many forms over the days to come, particularly as his daily lineup card is an evolution in and of itself.

While McMahon (and Tapia and Tauchman) represents the amount of capable young depth within the organization, it’s Ian Desmond who might most clearly define the model that Bridich and Black are now busily constructing. Desmond, a former Gold Glove shortstop who’d been converted to an outfielder before signing with the Rockies, was sold on the notion of playing first base in Colorado. It’s an unusual path, but one that will likely become more “normal” under Bridich’s watch. In an injury-riddled 2017 campaign, Desmond ended up playing first base (27 games), left field (66), centerfield (1) and shortstop (1).

Black cites this model’s versatility, options that would help any manager. But a deeper look into the impetus of Colorado’s new focus on both depth and flexibility begins with the team’s nasty history of injury. It has been long believed that it’s difficult for Rockies to remain healthy, or perhaps more importantly recover, while playing at altitude. Over a 15-year span (2001-16), the Rockies consistently spent plenty of time on the disabled list; according to fangraphs.com, Colorado ranked eighth among all MLB teams when it came to total man-games lost to the DL.

Whether that’s training methods, altitude or simply bad luck, it looks as if Bridich has essentially accepted the fact that injuries in Colorado happen. So, he’s building a roster that’s designed to lessen the impact of key players getting hurt.

The model is also built for situational baseball. If Black needs a faster baserunner, he’s probably got one on the bench, and that player is likely capable of playing more than one position. If he needs to play the lefty-righty matchups, the same theory applies. And in the event the pitching staff becomes thin or worn down, the depth at nearly every position outside of pitcher might allow Black to temporarily hold more hurlers on the active roster, just in case.

“Interchangeable” might best describe over half of the position players on the Rockies’ roster.

Perhaps that’s best illustrated by the official depth chart released by the team two weeks prior to the start of the season. Nine position players are listed as playing only one position, and three of them are catchers: Blackmon (CF), Gonzalez (RF), Cuevas (RF), LeMahieu (2B), Story (SS), Arenado (3B), and Iannetta, Tony Wolters and Murphy (all catchers). There are six position players, however, whose names appear at more than one position: Tapia (LF, CF, RF), Gerardo Parra (LF, RF), Tauchman (LF, CF), Pat Valaika (3B, SS, 2B, 1B) and McMahon (1B, 3B). Even amongst the “one-position” players, Blackmon, Gonzalez, LeMahieu, Wolters, and even Iannetta have all played multiple positions in a Rockies uniform.

A more concise way to view the Rockies’ approach to depth and flexibility is this: Be an All-Star at your position or play more than one.

Mar 4, 2017; Salt River Pima-Maricopa, AZ, USA; Colorado Rockies first baseman Ian Desmond (20) tosses the ball to first base during the first inning against the Seattle Mariners during a spring training game at Salt River Fields at Talking Stick. Mandatory Credit: Matt Kartozian-USA TODAY Sports

The takeoff from Phoenix’s Sky Harbor Airport back to Denver brings with it a feeling that Colorado might very well have a contending baseball team – again.

It’s no fluke, and the answer to “Why?” rests somewhere in the construction of not only the Rockies’ 25-man roster, but in the farm system, as well. Yes, the Rockies are talented. Yes, ownership can no longer be dubbed cheap. Yes, someone has finally decided that pitching at Coors Field is not an impossible task. But it’s more than that.

It’s a team built on depth and flexibility. It’s a team built to withstand the rigors of playing at altitude. It’s a team built to win.