Thank you so much for sharing that with me. It must have been incredibly hard for you. Now, I am not a trained counselor, psychologist or law officer. But I am here to listen, believe you and support you. No one should ever have to experience what you have just gone through, and I’m going to make sure that together we get you the help you need.

It’s been nearly two decades since I first learned that mantra (or some basic iteration of it); for parts of five years through high school and college I was prepared to deploy it as a peer counselor and then resident assistant. And if someone aged 17 to 21 can be put in a position of trust that allows their peers (or anyone really) to disclose allegations of domestic violence, rape or suicide with the understanding that said person will be equipped to help them, there’s no reason that the head of a major Division I football program can’t effectively execute that same position of trust. My crisis intervention training took all of one week (repeated annually) and yet it sticks like glue to me to this day. Why? Because it is the right thing to do, and because in the grand scheme of things it takes so little effort that to not do it seems borderline immoral.

As I said before, I personally do not have the training to give you the exact help you need, but I am here to make sure that you get it.

Disclosing something so traumatizing and life-altering as domestic abuse takes courage. According to a recent Sports Illustrated article, Joe Tumpkin’s girlfriend reportedly suffered two years of abuse before approaching University of Colorado head football coach Mike MacIntyre with the news that her now ex-boyfriend and MacIntyre’s now former safeties coach had physically, verbally and emotionally abused her. According to the SI report, Tumpkin’s victim took this allegation to MacIntyre, a mandatory reporter by CU policy, partly because she trusted the coach and partly because she didn’t want this situation to become a blight on Colorado’s recent success. The Buffs, after all, had shocked the nation and were suddenly a top-25 team that had just played for a Pac-12 title. She only wanted Tumpkin to get help, according to the report.

It is incredibly brave that you came to me with this information. I am so thankful that you trust me enough to share something so personal and difficult, and that you trust me enough to help you in this situation.

Give MacIntyre some credit in the way he handled the situation. According to SI, the head coach was kind and compassionate in his initial conversation with “Jane” (the name SI gave her to protect her anonymity) on Dec. 9, the week after Colorado had lost to Washington in the Pac-12 Championship. “You were very courageous to make this call,” MacIntyre reportedly told her.

Before we discuss this any more, I need to ask you if you feel safe. Not only right here and right now, but when this conversation is over.

Jane told SI that MacIntyre indeed asked her if she felt safe. Credit MacIntyre again. She told him she did – so long as Tumpkin didn’t lose his job. In fact, MacIntyre repeatedly reconfirmed that she felt safe. Kudos to MacIntyre for this.

Because I am not a trained counselor or officer of the law, I’m not going to be the person who can help you the most right now. As hard as this may be, we’re going to have to take this to someone more qualified than me to help you. Because of my position, I’m required to report this.

Here’s where things started to go off course. Between a pair of conversations over two days with Jane, MacIntyre confided this information with his direct supervisor, CU athletic director Rick George. MacIntyre confirmed this in a statement released Feb. 9. According to SI, he acknowledged as much to Jane, saying also that George was traveling but he and George would soon sit down and come up with a plan. Chancellor Phil DiStefano was notified shortly thereafter. None of those three went to the police (Jane had asked MacIntyre not to), nor did they seek additional counsel from university resources at their disposal. All three failed to take the matter to the school’s OIEC office, the university division whose responsibility it is to handle these kinds of situations. In a statement issued in response to the SI article, DiStefano said that all mandatory reporters (including MacIntyre and George) should hereafter report any allegations to the university’s office of Institutional Equity and Compliance (even in cases where the complainant is not a student, faculty or staff member and where the alleged abuse did not occur on campus, as was the case with Jane).

Even though we’re going to take this to someone more qualified, I will not only be there for you, I will be there with you if you need me. And I will be there for you afterwards.

Here’s where things really start to go downhill for MacIntyre in the way he handled the situation. After those two initial phone calls, Jane said she expected to hear from MacIntyre or George, or at least a victim’s advocate from the university. Instead, she heard from a lawyer – a lawyer who repeatedly asked what she wanted (money? treatment? an apology?). What she wanted, it seems, was for MacIntyre – a man she trusted with this information – to help her through this ordeal. The lawyer told her that she would not be hearing from MacIntyre again because the coach did not want to be called in as a witness. MacIntyre passed the point of no return with that decision. Despite being a mandatory reporter for the university and having a personal relationship with Jane, it was an action that appears rooted in self-preservation on MacIntyre’s part.

Throughout this process I promise to listen to you and protect your privacy.

Instead of going to the university office charged with handling allegations of this nature, MacIntyre, George and DiStefano turned to a lawyer. Specifically, one with a reputation for getting members of the CU football family out of trouble (although DiStefano was very clear in his statement that the lawyer is not being paid by university funds). More specifically, one who identified himself to Jane as Joe Tumpkin’s criminal defense attorney, Jon Banashek. Not only did MacIntyre fail to maintain his role as confidant, someone from the CU power triumvirate (MacIntyre, George and DiStefano) took this information straight to a person who would undoubtedly take it to her assailant. All while she waited for what she thought was forthcoming support from MacIntyre and the university – support that never came.

And I will do everything in my power to honor and respect just how difficult all this must be for you. I will be just as honest with you throughout this process as you have been with me.

MacIntyre’s final failing in this whole unfortunate situation came when on Dec. 16 – a week after his initial conversation with Jane – Tumpkin was announced as the defensive play-caller in the team’s upcoming Alamo Bowl, a move made in the wake of defensive coordinator Jim Leavitt’s departure to Oregon. DiStefano defended the school’s decision to not suspend Tumpkin when the allegations of abuse were first disclosed “because there was no restraining order, criminal charges, civil action or other documentation of the allegation.” What there was, however, was a devastated victim who had her situation made even worse to learn that not only was her alleged assailant not receiving the help she felt he needed, but he was instead being put into a spotlight role heading into the team’s biggest game. Even if the decision to give Tumpkin these duties had been made prior to these allegations being levied, all parties involved (including Tumpkin, who knew by that time what was happening, given his lawyer’s involvement) could and probably should have recognized that discretion is the better part of valor given the circumstances. The move left the victim feeling helpless and alone.

***

According to Chancellor DiStefano’s statement, he, MacInytre and George followed university policy to the letter. Per my own experience in a similar role, and my understanding of SI’s report and DiStefano’s memo, MacIntyre violated the spirit of what a mandatory reporter is supposed to be. Whether it’s a peer counselor, a resident assistant, the head football coach, the athletic director or anyone else, a mandatory reporter in this setting has an obligation to watch out for the well-being of the vulnerable, no matter how it may disrupt their own life and regardless of their relationship with the other party.

In cases of domestic violence, rape or suicide, failure to report can be the difference between life and death. It may seem easier said than done, but that’s a responsibility of the job as a mandatory reporter. And if that’s a part of the job you’re unwilling to do, there are countless others equally as qualified who are willing. Furthermore, if the University of Colorado failed to provide Mike MacIntyre that training or comprehensive understanding of that obligation, they are equally responsible for mishandling this situation.

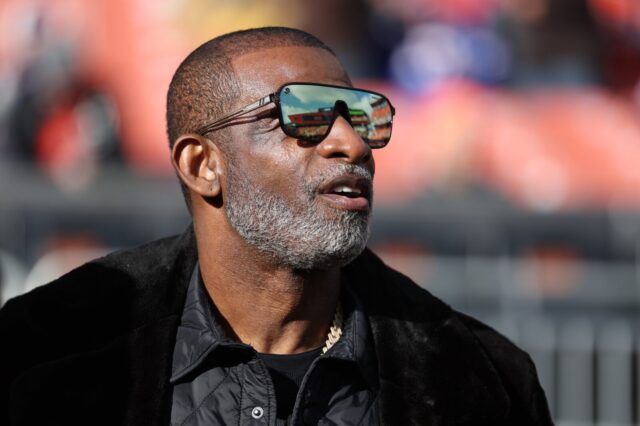

Throughout Colorado’s outstanding 2016 season, MacIntyre used the rallying cry “Players make plays, players win games,” to motivate his team. The mantra meant simply that he and his staff would put his players in the position to win, so long as they executed the game plan. As a mandatory reporter, the game plan should have been to take allegations of abuse to the OIEC regardless of the victim’s status with the university or the physical location where the abuse occurred. Given his personal relationship with Jane, MacIntyre’s own game plan should have included being honest and transparent with her. Both of those game plans would have likely resulted in relative “wins” for Jane, MacIntyre and the university (not that there is ever a winner in cases of abuse). Instead, all three parties found themselves on the proverbial losing side.

Jane was compelled to make her story public in order to find emotional justice (the legal proceedings will take much longer). MacIntyre, George and DiStefano have suffered a collective black eye, even if they handled the situation correctly according to the strictest interpretation of their mandatory reporting policy. And the University’s policy was shown to have a serious hole in terms of victim protection.

Fortunately, it appears each of those things is on its way to being made right. Sadly, it took this whole affair becoming public for that to happen – precisely what Jane didn’t want to begin with.

In his statement, MacInytre wrote the following:

I did not come to CU to run a program or to achieve success at any cost. Nor has the CU leadership ever encouraged such behavior. I can assure the campus community, all CU fans and all of our student-athletes and their families that I personally (and our team and coaching staff collectively) will continue to build the rise of CU football on a bedrock set of values: decency, honor, excellence, respect for women and for all people being chief among them.

MacIntyre is, by all accounts outside of this sad situation, a good man. Why else would Jane have trusted him with such tragic and important information? He is not a perfect man, though. And his mishandling of this situation will no doubt stick with him for the rest of his life.

Those words of compassion and understanding I paraphrased earlier, and the actions that must follow them – which I learned nearly 20 years ago – stick with me to this day. It is my sincere hope that this saga will also stick with you and motivate you to get some simple training in how to handle such a situation should one like it find its way to you.

For more information on supporting victims’ rights and preventing domestic abuse in Colorado, please visit the Colorado Department of Human Services’ county by county directory. Nationally, the CDC provides these resources for preventing domestic violence along with their VetoViolence Facebook Page. Other resources include the National Domestic Violence Hotline, the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline and the National Teen Dating Abuse Helpline.