This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition.

The common refrain for most autumns around these parts is that, while we’ve got some NFL and Division II cred, our dreams of competing in those elusive College Football Playoff bowl games are too often short-lived.

Yes, this year can always be different, but if the last 25 years are any kind of indicator, the chances of the University of Colorado (despite toying with our emotions last year) or Colorado State and Air Force, from the generally disrespected Mountain West, going to the College Football Playoff National Championship Game are as remote as a traffic-free weekend drive down I-70 during ski season.

But wait. On further review, Colorado did play a major part in the College Football Playoff National Championship Game on Jan. 9, Clemson’s classic, last-second 35-31 win over Alabama before 74,512 mesmerized fans at Tampa’s Raymond James Stadium and 26 million television and screaming streaming viewers.

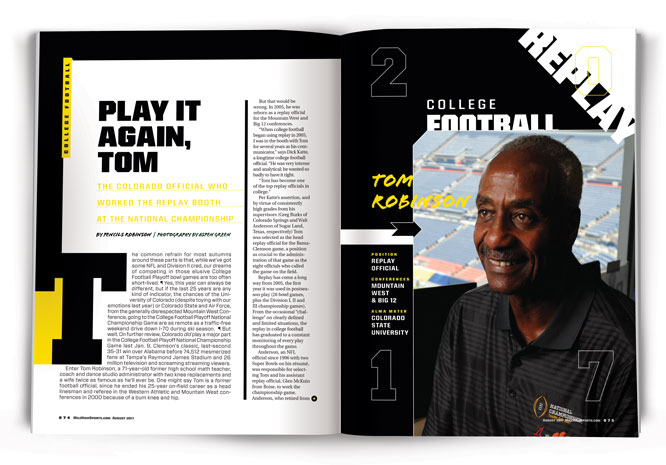

Enter Tom Robinson, a 71-year-old former high school math teacher, coach and dance studio administrator with two knee replacements and a wife twice as famous as he’ll ever be. One might say Tom is a former football official, since he ended his 25-year on-field career as a head linesman and referee in the Western Athletic and Mountain West conferences in 2000 because of a bum knee and hip.

But that would be wrong. In 2005, he was reborn as a replay official for the Mountain West and Big 12 conferences.

“When college football began using replay in 2005, I was in the booth with Tom for several years as his communicator,” says Dick Katte, a longtime college football official. “He was very intense and analytical; he wanted so badly to have it right.

“Tom has become one of the top replay officials in college.”

Per Katte’s assertion, and by virtue of consistently high grades from his supervisors (Greg Burks of Colorado Springs and Walt Anderson of Sugar Land, Texas, respectively) Tom was selected as the head replay official for the Bama-Clemson game, a position as crucial to the administration of that game as the eight officials who called the game on the field.

Replay has come a long way from 2005, the first year it was used in postseason play (28 bowl games, plus the Division I, II and III championship games). From the occasional “challenge” on clearly defined and limited situations, the replay in college football has graduated to a constant monitoring of every play throughout the game.

Anderson, an NFL official since 1996 with two Super Bowls on his résumé, was responsible for selecting Tom and his assistant replay official, Glenn McHughen from Boise, to work the championship game. Anderson, who retired from his dental practice after he was named an NFL referee in 2003, had this to say about Tom and his work in the title game:

“I had the privilege of watching that game in the replay booth and observed firsthand the great work Tom did throughout the game … Few people realize that with the pace of today’s college game, the replay official has only seconds on each play to make the determination of not only if the play was officiated correctly, but if any specific aspect of the play is reviewable and meets the strict criteria necessary to stop the game. Tom and his crew in the booth did an outstanding job and we are all very proud of him and his performance.”

The earlier concept of a replay official as an old guy in the booth checking a few monitors for the occasional challenge is outdated, except maybe for the “old guy” part.

“We had 221 plays in the game, and I had to confirm every play,” Robinson noted two weeks after the game, while sitting in his office at the Colorado High School Activities Association in Aurora where he is now beginning his 17th and possibly final year as the CHSAA’s officiating liaison and associate commissioner (to newly appointed commissioner Rhonda Blanford-Green).

“This is what happens mechanically: All of the officials have a pager, and the only time the game gets stopped is when I stop it. So, I have to confirm the ruling on the field, whatever it is. If it’s a catch, I have to confirm it. If they rule that he didn’t fumble it, I have to confirm it. I have to have video evidence of what happened. On every play – every single play. Thirty-nine camera angles, supplied by ESPN, were available to us.”

In a game of such intensity – “Tom’s ability to remain calm in stressful situations is exactly what a successful replay official needs,” says Jack Lynch a friend and former football coach – that was not decided until the final play, there seemed to be little controversy, even over the pass interference call on Alabama defensive back Anthony Averett that placed the ball at the 2-yard line with six seconds left in the game.

“Because I have enough to do in my own realm of the game, I usually don’t weigh in on judgment calls made by the on-field officials,” Robinson said. “But if you look at this potential OPI (offensive pass interference) play and another situation earlier in the game, the on-field crew got it right. The defense in both scenarios initiated the contact.”

Tom felt a particularly complex call – or no-call – early in the game involved a Clemson receiver making a catch and trying to get out of the grasp of the tackler when he gets clocked by another Alabama defender.

“If the contact that took place was with the crown of the helmet,” Tom explained, “I would have had to stop the game and then initiate the foul, which would lead to the ejection of the player for targeting. When we looked at it, we felt like the receiver had become a runner and that the only way that it could be targeting would be if the defender hit him with the crown of the helmet and was trying to launch at him. We saw the contact from the side of the helmet and without an attempt to launch at the runner and thus it was not a targeting foul.”

Tom’s satisfaction with his officiating goes beyond the praise of his supervisor or the general lack of discussion about the game’s officiating (every official’s ideal). Just as he was as a high school and college athlete, Tom performed best on the biggest stage.

“One thing I’ll always remember about coaching him in basketball,” says Guy Gibbs, Tom’s high school basketball coach at Regis, “was that he had trouble with free throws during practice, but never in a game.”

With regard to this particular game, Robinson has an almost Zen-like recollection of his approach and performance in the booth. He recalls:

“I’ve been in a lot of big games over 25 years. I remember being a little nervous before an Oklahoma-Oklahoma State game. I figured it would be that way for this one, but it was more like an out-of-body experience. I was just tuned into the game. I knew how big it was going to be, but when I was making calls I didn’t have the mindset that I was dealing with a big game. Ever.

“Of course, in football you’re dictated by the plays and sometimes those plays create big dilemmas. But I told myself that you can’t worry about the stuff you can’t control. You can’t control the plays you get, you just have to look at them and make a decision. It was a special, special game. Special.

“I’ll probably remember every play all of my life.”

And it was special for Colorado to be represented by one of its own in one of the greatest national championship games ever played.