This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition here.

The sun always shines on Pueblo.

This late Sunday in June is no exception as hundreds of citizens of Colorado’s eighth-largest city move purposefully across the sweltering parking lot toward the promise of an air-conditioned hall in the Pueblo Convention Center.

Though the town has always prided itself on being blue collar/working class, many of the men, particularly those moving more slowly, are clad in dark suits set off by conservative neckwear. The ties are wide, with large and loosely gathered knots, and stop a few inches short of the waist. You can almost see the sweat gathering inside the stressed collars, rolling down the backs.

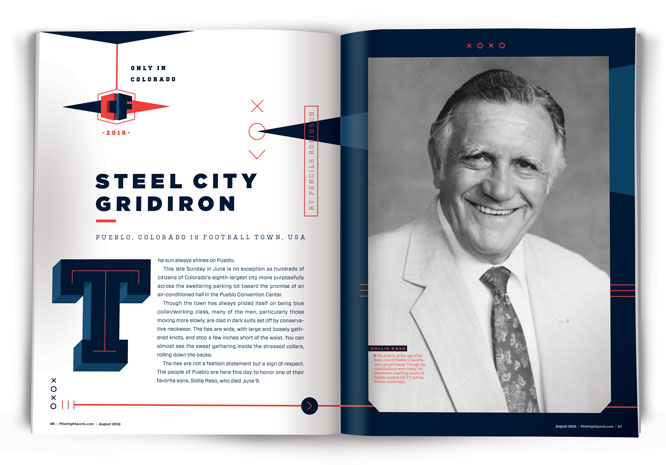

The ties are not a fashion statement but a sign of respect. The people of Pueblo are here this day to honor one of their favorite sons, Sollie Raso, who died June 9.

As is the modern custom, there are no forced tears, no wailing among the group that is here to celebrate Sollie’s 94-year, incredibly well-lived life. Although not a native Puebloan, Sollie long ago reached “local” status by deed and devotion. He was raised in north Denver but elevated in Pueblo. He in turn elevated the Steel City.

Sollie Raso was many things to Pueblo: A family man, a teacher, a high school principal, a juggernaut of a district athletic administrator and later, against all odds for a lifetime non-politician, a county commissioner.

He represented all of the things Pueblo has always valued – family, God, education and hard work. But what stood out as people spoke of his life was that he loved athletics as much as his town did. For all he did, for all the hats he wore so well, he was revered for something he did for only a small part of his career – just eight years – and that was coaching football (1948-55 with a 58-17 record). The former University of Colorado football and track letterman also coached basketball, wrestling and track at Pueblo Central High School.

Sollie’s oldest daughter, Debbie Lynch, has lined up five speakers who represent different parts of her dad’s life. Debbie was a longtime administrator in the Aurora Public Schools and married another administrator, Jack, who was the district athletic director in Aurora and a NCAA Division I football official for years. As Sollie’s daughter, she expects the proceedings to move in an efficient, orderly manner, like the state track meets her dad directed at Dutch Clark Stadium.

One speaker is Sam Pagano, a Pueblo guy who became Colorado football royalty. He won three state titles (1978, ’79 and ’87) during his 21-year tenure as Fairview’s head football coach. For 36 years, Pagano also directed the Mile High Football Clinic, a pioneering effort that had a huge impact on the quality of high school football (players and coaches) in Colorado. He coached his two sons who went on to successful coaching careers of their own. John began as an assistant with the San Diego Chargers in 2002 and has served as their defensive coordinator since 2012. Chuck began coaching in the NFL with the Browns in 2001; he then worked for the Raiders and the Ravens before becoming the head coach of the Indianapolis Colts in 2012.

Sam tells the Convention Center crowd what it was like growing up in Pueblo. “When I was 14, I couldn’t wait to report to football tryouts and get a chance to play for Sollie Raso and the Pueblo Central Wildcats. But then I was like almost every other kid in Pueblo.”

That note on the end of a great man’s life begins this story about a town that loves all forms of athletic completion, but particularly that uniquely American one – football.

***

Telling the story of Pueblo football is so big it’s like trying to start a plate of spaghetti and sausage at La Tronica’s, Pueblo’s Abriendo Avenue mainstay Italian eatery since 1943.

The school of Sollie Raso and Sam Pagano, Pueblo Central, is as good a place to start as any. The Wildcats have won half (six) of the state gridiron championships claimed by Pueblo high schools, including the first one in 1928, the eighth year that CHSAA recognized high school football. Central, coached by Oscar Herigstad, defeated defending champ Fort Collins, which had won four of the first state titles.

Central went on to win state titles in 1938, ’44, ’47 and ’61 but hasn’t claimed one since its last championship in 1965. Central’s enrollment has steadily declined and its 769 students place it in the 3A (enrollments of 710-1,239) South Central Conference.

Despite its championship draught, Central remains in the football spotlight every year when it plays Centennial in the annual Bell Game, aka “The One Hundred Year War,” the oldest high school football rivalry west of the Mississippi. On Sept. 16 at 7 p.m. the two Steel City teams will meet at Dutch Clark Stadium for the 116th renewal (“Little” Jack Hopkins got punched during an end zone brawl in the 1907 game; the ensuing riot led to a 14-year cooling off period) of the game that began at Minnequa Ball Park on Thanksgiving Day in 1892 with a 4-0 (a touchdown counted four points then) Central win over its senior rival. Centennial was the first high school in Pueblo in 1873; Central opened ten years later.

The last two games, played before the usual 15,000 fans in the 12,500-capacity stadium have been what ABC broadcaster Keith Jackson would refer to as “stem-winders.” The Bulldogs won 28-26 in 2014 to establish the longest Bell Game winning streak at five. Central’s Wildcats earned the right to paint the bell (donated in 1950 by fan Lewis Rhoades from a Colorado & Wyoming Railway engine) blue by virtue of its 27-24 victory in 2015. Central leads the rivalry, which seems hardly diminished by the fact that the 1,261-student Centennial plays in the 4A (1,240-1,809) Southern Conference, 56-50 with nine ties.

The Bell Game isn’t the only game in town anymore, as Pueblo East and South have been playing in the Cannon Game since 1958 and resume that rivalry at Dutch Clark at 7 p.m. on Sept. 30. A more recent addition to the Pueblo rivalries is the Pigskin Classic, which will see Pueblo West travel to Pueblo County for a 7 p.m. contest on Sept. 16.

New Kid on Abriendo

East is the latest success story in Pueblo football, becoming the first public school in the city’s history to win back-to-back state football titles. They did it with two different head coaches and, amazingly, will try for a three-peat with yet another new coach this year.

Centennial grad David Ramirez guided the Eagles to the 2014 3A title with a 30-14 win over Rifle but abruptly resigned shortly after the season. He was an assistant at Liberty (Colorado Springs) last year and is the new head coach at Sand Creek for 2016.

Lee Meisner, a Sterling High star and All-America linebacker at CSU-Pueblo, took the reins in 2015 and led the Eagles back to the promised land with a 57-31 finals win over Roosevelt before 7,245 fans at Dutch Clark. He too resigned after the season.

Andy Watts, an assistant at East before and during both championship seasons, was hired in February as the Eagles’ new head coach.

Pueblo’s Greatest Player

That name Dutch Clark keeps surfacing and we haven’t even begun to talk about the great players who have graced the Pueblo high school football fields for the past 125 years. In 1980, Dutch Clark’s name was placed on the Pueblo District 60 Stadium (with help from Sollie Raso, whose name many feel should be on the other side of a hyphen with Dutch) for a reason.

There was and still is an aura about Dutch Clark-Sollie Raso Stadium (just trying that name on for size). Dave Socier, a Pueblo Catholic grad, who covered high school sports like a velvet blanket from 1972 to 2005 for the Pueblo Chieftain noted recently: “Kids from Denver coming to play Pueblo at Dutch Clark would get off the bus and look through the fence at that beautiful track and all those seats and say to their teammates, ‘You gotta see this place.’ That stadium awed a lot of visiting teams.”

“Any discussion of who ranks as the best football player in Pueblo history begins and ends with one name: Earl ‘Dutch’ Clark,” wrote Mike Spence in an exhaustive July 18, 2006 Chieftain article about the all-time gridiron greats of the Steel City.

Dutch no doubt had a lot to do with maintaining Pueblo’s interest in football at a fever pitch. He led Central to the state semifinals in his junior and senior years, 1924 and ’25, as he scored all of the Wildcats’ points in losses to La Junta both years. In the 1925 Bell Game, Clark’s Central Wildcats played before the largest crowd – 3,500 fans – to watch a sporting event in Pueblo up to that time. Central shellacked Centennial 43-0 with Dutch rushing for four touchdowns and passing for two more.

Football wasn’t his only game, either. Dutch lettered four times each in football, basketball, baseball and track. He led Central to the state hoops championship in 1926 and a second-place finish in the national high school basketball tournament that year.

Dutch Clark was a big deal in Pueblo, one of a long line of high school heroes. What makes him so special? In his junior year at Colorado College, Clark became the Colorado Springs school’s first All-American in 1928.

If there was still a perception that Clark was just a small-time hero with bad vision (20/100 and 20/200), his inclusion in the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s inaugural class of 17 men (including Sammy Baugh, Red Grange, George Halas, Bronko Nagurski, Ernie Nevers and Jim Thorpe) in 1963 cements his status as one of football’s all-time greats.

College Football in Pueblo

Much has been written about the rise to national prominence by the CSU-Pueblo ThunderWolves, including a MHSM piece that appeared in the August 2015 issue. Undoubtedly one of the lowest points in the city’s football history came in 1985 when then-named University of Southern Colorado dropped intercollegiate football, a program the school had sponsored, with three years off during WWII, since 1938. Through the work of the DeRose family and the Pueblo community, the program was reborn in 2008 and debuted in the 6,500-seat Neta and Eddie DeRose ThunderBowl.

John Wristen, a three-time all-conference quarterback at Southern Colorado from 1980-83, was hired in 2008 facing the momentous task of reviving the defunct program. Seven years later he was hoisting the NCAA Division II national championship trophy after beating Minnesota State-Mankato 13-0 in Kansas City. Coupled with Pueblo East’s 3A state championship three weeks earlier, Pueblo was once again bathing in gridiron glory.

Wristen’s rise from startup to national champion is nothing short of remarkable. After a 4-6 record in 2008, the ThunderWolves have not had a losing season. Wristen’s eight-year tally is 80 wins and 18 losses. One of great aspects of the CSU-Pueblo football program is that it demonstrates the quality of the state’s high school football programs. Wristen’s 2015 roster listed 74 Colorado kids (including seven from Pueblo) out of 120 players.

Minor League Football in Pueblo

Perhaps they are just a footnote in history, but the Pueblo Crusaders were born when Dan DeRose bought Southern Colorado’s dust-gathering football equipment for $1,500 in 1987. This is the same DeRose who spearheaded the drive to return college football to his alma mater where he was an All-American linebacker in 1983. He was good enough to be signed as a free agent by the Broncos but didn’t play. He had a brief NFL career as the defensive captain of 1987 New York Giants strike replacement team.

“The Cru” as they came to be known by the crowds at Dutch Clark Stadium went on to win the first championship of the 10-team Minor League Football System in 1989, downing the Colorado Springs Spirit 21-14. The Crusaders, led by middle linebacker/owner DeRose, advanced to the final game in the final year of the MLFS, but fell 24-18 to the Charlotte Barons.

From the Outside Looking In

From the beginning of this piece I’ve had an uncomfortable feeling of being a voyeur, a poser, a condescender, even a plagiarizer. I’ve read great stuff about Pueblo from Chieftain writers Mike Spence, Jeff Letofsky and Joe Cervi and pieces by Denver Post writers Irv Moss and Nick Groke. I’ve combed the CHSAA record books and Hall of Fame programs artfully written by Bert Borgmann. I’ve talked with one of the Chieftain’s most engaging writers since Damon Runyon (who began his literary career as a “sporting writer” for the Pueblo Star in 1900), Dave Socier, and one of its great sports editors Judy Hildner, who along with her late husband Jack (both editor and sports editor) is a member of the Greater Pueblo Hall of Fame.

I bet I’ve spent close to a cumulative year in Pueblo since I started attending state tournaments – baseball, track, cross country, golf, tennis, football – there in 1972, not to mention the times I’ve driven down there or stopped on my way to Taos to eat a Pass Key Special Italian Sausage sandwich, or have the Dutch lunch at Gus’ Place in the Bessemer neighborhood or huevos at the Mill Stop.

But I’m a still a Denverite pretending to understand and write about a city in which I have never lived. I have no idea what it was like living in a boom-time steel town that at its peak in the 1980s that saw over 13,000 Puebloans report for work each morning at the C.F.&I. (Colorado Fuel and Iron) steel mill. Or what it was like when the mill jobs and the railroad dried up in the 1990s, when Pueblo, once the second-largest city in Colorado, fell to eighth and school enrollments began to fall to the point where none of the city’s schools were in the state’s top 5A classification.

I’ve always loved the diversity of the town and the stories of how the Italians, the Latinos and the Bojons all got along and shared a common goal of building a great community and great athletic teams. Those stories could be more apocryphal than true, but since I have always been “just passing through,” I really don’t know.

I do know this. Early on, Pueblo became my favorite city in Colorado. I loved the food, the weather, the reasonable prices, the sports facilities, but most of all I loved the people. I’ve never felt more welcome in a city than I have in Pueblo; I never once felt like a stranger.

There was always something a little different about the Pueblo athletes, coaches, officials, sportswriters and even the administrators involved in high school athletics. They were competitive as hell. They were damn good because they worked at it and never apologized for making sports an integral part of their school system. But, geez, they played fair. And the kids conducted themselves with class. The guys seemed like the kind of young men you’d like to have marry your daughter. (Note to dads whose daughters are considering marrying a Pueblo athlete: Generalizations are inherently flawed.)

An attitude must have started before Sollie Raso – maybe it began with Dutch Clark or his coach at Central, Oscar Hergistat and continued with Ernie Ballotti, John Rivas and Fred Rodriguez, gentlemen who followed Sollie as Pueblo 60’s district athletic directors – that became a part of the collective athletic ethos of the town. The ethos says: Play like hell to win for your school and Pueblo; respect your opponent and the game; and never ever make an excuse when you lose.

There’s something, too, about Pueblo natives who have relocated to other cities. No matter how long they’ve been gone they’re still from Pueblo. They still know who won the Bell Game; they celebrate CSU-Pueblo’s rise to national prominence in college football; they know that Pueblo East won consecutive state titles. And they always return. There’s no other town in Colorado in which residents, past and present, take such pride in their birthright. They say, “I grew up in Pueblo (without adding Colorado).” And there’s a look in their eye that says you – and everyone else – know it’s a special place.

Pueblo’s population has dwindled and the schools no longer play in the state’s highest classification, but football still matters every autumn Friday and Saturday in this most resilient of Colorado towns. Just as it did when Dutch Clark played and Sollie Raso coached.